When should you quit?

It's natural for entrepreneurs to work on multiple projects. Starting a new project is easy; but you also need to learn how to quit a project.

In the past, I've written about the importance of persistence. A reader, Stuart, replied and said:

This is good. But you should write about "when to give up" too. Not everything is worth pursuing for ten years. How do you know whether to keep fighting or not?

He's right. There's value in building something patiently, and grinding through the resistance. But there's a flipside to that coin:

Sometimes, you need to quit a project and move on.

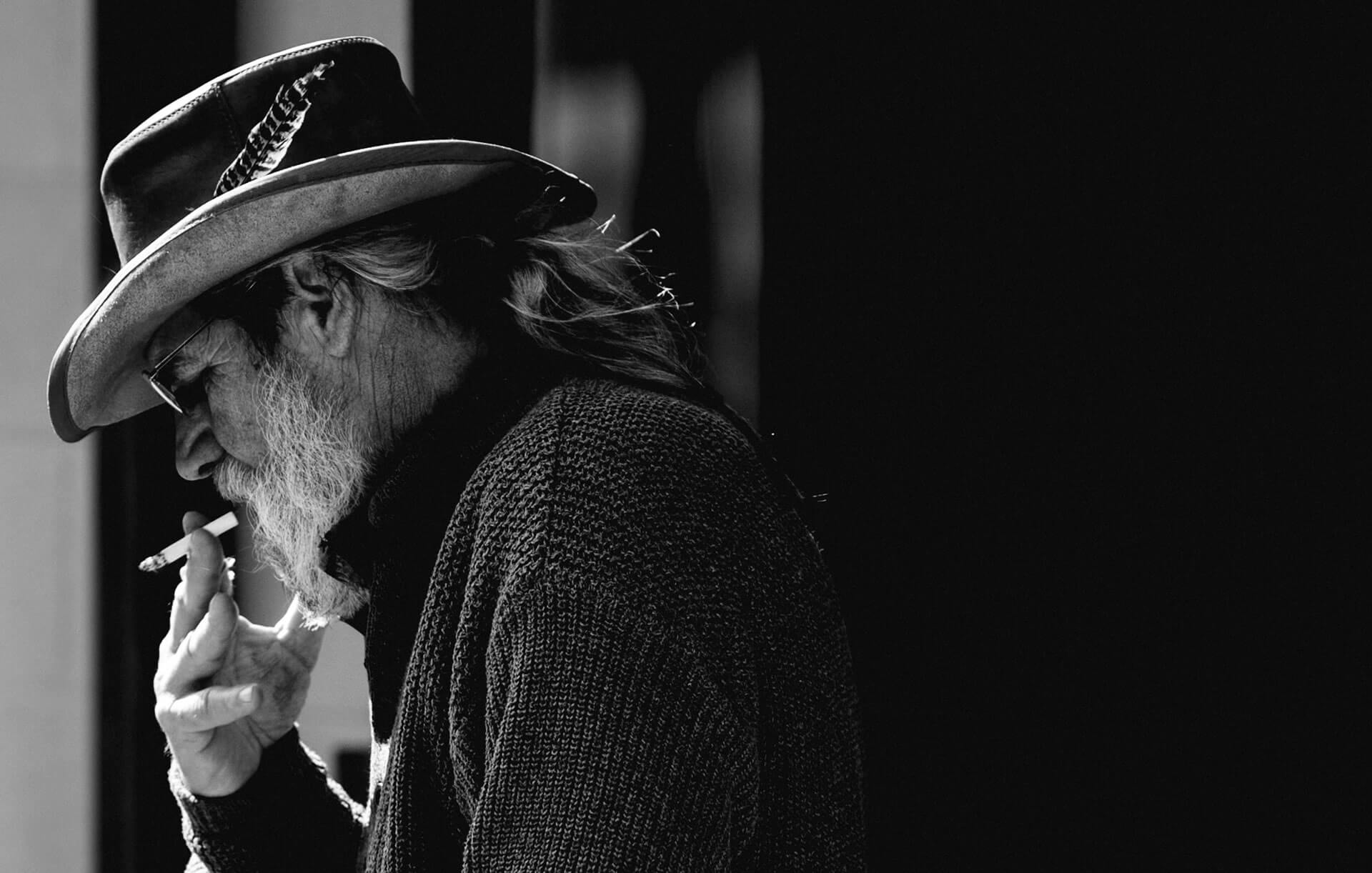

This is the central tension in Don Schlitz's famous country song, "The Gambler:"

But "The Gambler" never answers that question: how do you know when to fold, and when to walk away?

Experience is a good teacher

One thing about being a poker player, is that if you play a lot, you start to get a sense for when it's time to fold.

If you're still early in your journey, you might not have played enough hands yet to know the difference between folding too early, or folding too late.

When Taylor Otwell (the creator of Laravel) launched his first paid product, nobody showed up.

"My original idea was to create an invoice manager for lawn companies. In 2011, I built it with another guy. We called it Coin Fly. We launched it, and we used it, but no one else signed up."

Taylor kept building things. Three years later, he launched Forge, and got a very different reaction:

Within a month it had about 1,000 customers.

The advantage of launching sequential projects is that you can feel the difference between a "hit" and a "miss."

Taylor's experience isn't unique. Many of the founders I know experienced something similar.

Derek Sivers was trying to make it as a professional musician for years. In this post, he describes the grind:

I had spent twelve years trying to promote my various projects. It always felt like an uphill battle, trying to open locked or slamming doors.

Then, in 1997, he created a company called CD Baby. And it became a crazy success. He later said:

For the first time in my life, I had made something that people really wanted. Don’t waste years fighting uphill battles against locked doors. Improve or invent until you get that huge response.

Good businesses have a momentum that's hard to describe. It doesn't always show up right away. For Disney, it took ten years. When Nathan Barry launched ConvertKit, he spent three years before he got the response he wanted. MailChimp was a side-project for six years.

But, eventually, you should see positive traction.

What does traction look like? Early on, you can evaluate your idea's potential by looking at:

- How many people respond

- How enthusiastically they respond

One thing that kept Walt Disney going during the hard times was seeing the effect his cartoons were having on audiences. People loved them. Even though the money wasn't there (yet), that gave him enough fuel to carry on.

An enthusiastic response is a good start, but it's not enough.Eventually, you should see lots of strangers lining up to buy your product. Jason Lemkin says that for SaaS companies that means "around $8k MRR / $100k ARR."

Most important: if you have something people really want, you shouldn't have to put a massive amount of effort into convincing them to buy. Yes, it will take some effort to position your product correctly. Yes, you might need to find the right distribution channels. But ultimately, people should be coming to you on their own. It shouldn't feel like a grind. Like Derek Sivers says:

Instead of trying to create demand, you’re managing the huge demand.

How long should you wait for that to happen? That's up to you. It usually depends on how much time, money, and energy you have left.

Also, the internet has given us the ability to research a market, develop a hypothesis, and test our ideas faster than ever before.

Jason Cohen wasn't willing to start building his product until he found people willing to write him a check first:

I had an idea before WPengine, but I couldn't find enough people to give me money and so I gave up. But with WPengine, I was able to find 30-40 people who agreed to give me $50 a month if I built it.

Jason also thinks startups shouldn't wait too long before pulling the plug. "It’s difficult to find successful companies where it took longer than four years to get to $1M ARR," he told me, "if you're two years in and you still need a day job then by definition it doesn’t have good fundamentals."

But how do you know when to give up?

I realize there's tension between all these ideas.

On the one hand, persistence is essential. We don't want to flit from one idea to the other. We don't want to give up too quickly.

"Before you sell, before you quit, before you step down, remember: at best, we have 3 real start-ups in us as founders.Often just 1 or maybe 2.If you have any traction at all -- maybe find a way to make this one work." – Jason Lemkin

But on the other hand, traction is important. We don't want to waste too much time, energy, and money on a bad idea.

"If multiple people are saying, 'Wow! Yes! I need this! I’d be happy to pay you to do this!' then you should probably do it. But if the response is anything less, don’t pursue it." – Derek Sivers

This, of course, is what makes business hard.

How do you know when to fold, and when to walk away?

Maybe, this is like poker.

Instead of needing every project to be a "success," our focus should be on consistently getting better at the game.

That's what my friend Peldi did before he started Balsamiq. He was working at Adobe at the time, and he was terrified of quitting his job to start a company. So he reframed his definition of success. This is what he told himself:

"My goal is to spend a year (or two if I can) learning as much as possible about what it's like to start a software company. Regardless of whether the company succeeds or not financially, I will still be winning, because I'll have learned what to do and what not to do."

If we put our effort into continually getting better, sooner or later, we'll win big.

I hope this helps!

Cheers,

Justin Jackson

@mijustin

PS: my friend Derrick just published an in-depth retrospective on why he decided to walk away from a product he'd been working on for a year.