Is the Product-Market Fit survey accurate?

Would I feel disappointed I could no longer use Slack?

In our company, Transistor, Jon and I use Slack every day to communicate. I'm also a member of numerous groups that use Slack.

When I initially started using Slack, I loved it. The interface felt playful and fun. Plus, all my peers were using it.

But now, like many others, I've grown weary of it.

However, my weariness isn't enough to make me stop using it. I wonder: how disappointed would I be if it went away?

The Product/Market Fit Survey

In 2009, Sean Ellis used this same question to determine if Dropbox had product/market fit:

"How would you feel if you could no longer use the product?"

He gave respondents four choices:

- Very disappointed

- Somewhat disappointed

- Not disappointed (it really isn't that useful)

- N/A (I no longer use the product)

His benchmark for product/market fit was if 40% (or more) of respondents replied that they would be "very disappointed if they could no longer use the product."

Using the survey is considered a "best practice" for Product Managers, analysts, and founders. I've personally used it for different startups I've worked with. I've also recommended it here, in the past:

It seems especially helpful for early-stage products.

But, as I observed above, the results might not be as useful for more mature products.

Limitations of the Product/Market Fit Survey

The survey has limitations that product people should be aware of.

First, it asks customers to guess about their future feelings.

As Rob Fitzpatrick points out in his book, their answers could lead you down the wrong path. He points out that humans are generally bad at forecasting their future behavior.

When a customer responds to your product survey and says: "I'd be very disappointed if your product went away," they're guessing. In the future, if your product does go away, they might find that it doesn't bug them that much!

For example, even though I rely on Slack every day, I might be relieved if it went away. Not having constant interruptions and notifications might make my life better.

Likewise, I remember thinking I'd be upset when Microsoft acquired Sunrise Calendar and announced they'd be shutting it down.

But, when they did remove my account, I just moved to Google Calendar, and I was fine. Any feelings of disappointment disappeared pretty quickly.

Alternatives to the Product/Market Fit survey

In "The Mom Test," Rob advocates for asking a different type of question:

"Ask about what they already do now, not what they believe they might do in the future."

He doesn't mention the Product/Market Fit survey directly, but I believe the principle applies here as well.

Instead of asking, "how disappointed would you feel?" we could ask:

- "Has the product ever been unavailable?" (Due to an outage, or other reason)

- "How did that make you feel when you couldn't use it?"

- "How did it affect your productivity?"

- "Did you search for alternatives?"

An outage is a real event in the past. We don't have to guess about how we'd feel, we know.

You can search "Slack is down" on Twitter and see tons of examples of how people react.

The most common reaction to Slack being down?

"Oh cool, I can get some work done!"

This is the kind of sentiment that may not show up on Product/Market Fit Surveys.

It sounds like many folks would be “relieved” if they could no longer use Slack.But that doesn't mean they don't have product/market fit. Their customers will continue to use Slack because it’s entrenched in their company culture and processes.

Our allegiance to the present solution

My friend Derrick Reimer learned how rooted Slack users were in their current behavior when he tried to build a competitor:

The gap between interest and implementation was of canyon-like proportions. Small teams didn’t seem that compelled by Level. In follow-up conversations, I discovered that Slack was at most a minor annoyance for them. Suboptimal? Yes. Worth going through the trouble of switching? Probably not.

To me, this "allegiance to the present" is a clear sign of product/market fit. Folks are annoyed by Slack, but they're not willing to give it up.

Our allegiance to products is often irrational:

- People will buy a Tesla because they're fans of Elon Musk.

- I've continued to use Adobe Fireworks CS5, out of habit, despite it being 10 years old.

Dan Ariely is a behavioral economist at MIT. In his book, he spells out our fallibility:

Standard economics assumes that we are rational. But, we are far less rational in our decision making. We all make the same types of mistakes over and over, because of the basic wiring of our brains.

We often design surveys assuming that humans will answer honestly. But Ariely's viewpoint is congruent with Rob Fitzpatrick's:

Individuals are honest only to the extent that it suits them (including their desire to please others).

When doing product research, we need to assume that folks are being dishonest (or at the very least, can't predict how they'll behave in the future).

What are the signs of product-market fit?

So if we can't rely exclusively on the product/market fit survey, what other tactics can we use?

Customer conversations

The most important step is to listen to your market. Grab a copy of The Mom Test, and start asking questions like:

- What solution are you currently using?

- How did you find it?

- What else did you try?

- What convinced you to try it?

Don't ask future-based questions ("Would you use this?"). Ask about what they're already doing, or have already tried.

You're looking for lots of evidence that people are searching for, trying, and buying solutions that perform a similar function to what you've built (or are thinking of building).

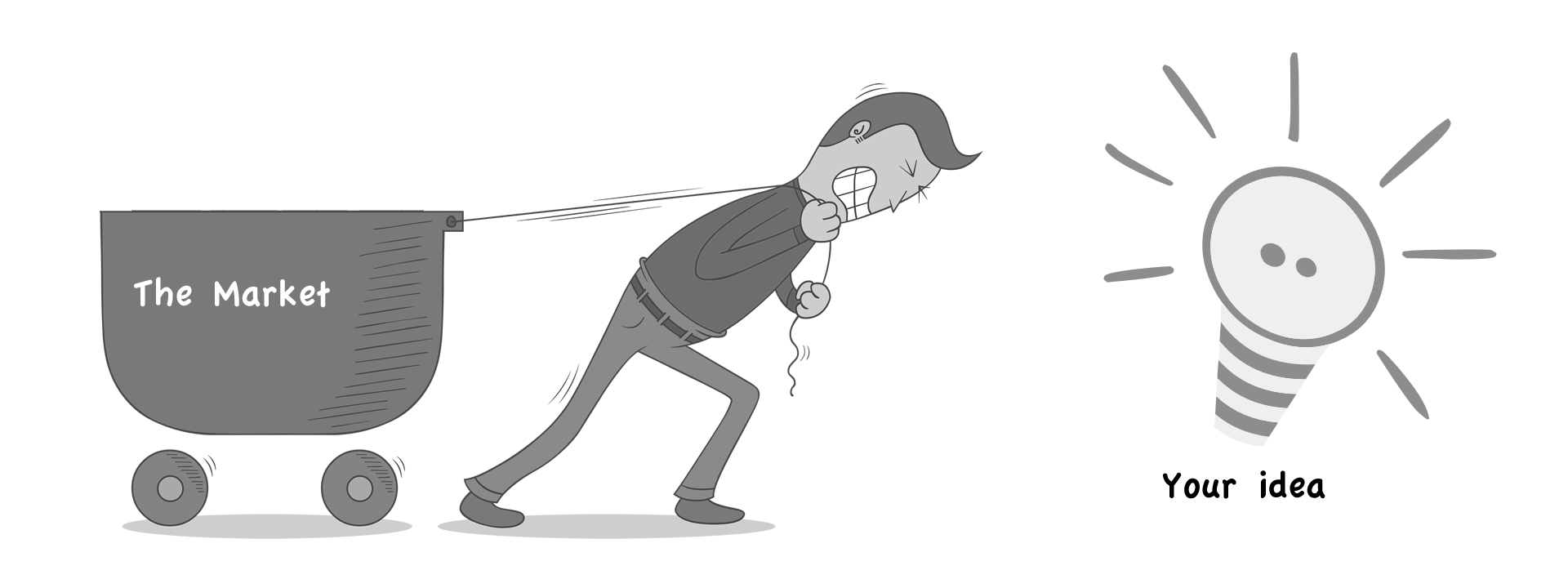

Also: don't lead the witness! Markets pull solutions towards themselves naturally; you shouldn't have to pull the market towards your solution.

In most cases, if you don't have enough information, it's because you haven't had enough conversations with potential customers.

Business metrics

Brian Balfour recommends looking at three business metrics:

- Top-Line Growth

- Retention

- Meaningful Usage

If you're growing at a healthy pace, retaining most of your users, and are seeing recurring usage from those users, Brian thinks that's a good sign of product/market fit.

I like this framework because it shows the importance of choosing the right market:

- Top-line growth comes from a market that's hungry for a solution.

- Retention and usage are both signs that you've built a good product for that market.

I hope this is helpful!

Justin Jackson

@mijustin