It's not just B2C vs B2B anymore

My story: "I must build a B2B SaaS"

When Jon and I started Transistor, a podcast-hosting platform, we followed the common bootstrapper wisdom:

"Don't build a B2C product; build for B2B. Consumers are a pain to support, have high churn, and low LTV."

We aimed to create the "WPEngine for podcast hosting" (WPEngine being a WordPress hosting platform targeting brands, businesses, and agencies).

Our initial slogans reflected this B2B focus: "The best way to create a podcast for your business" and "Podcast hosting for brands."

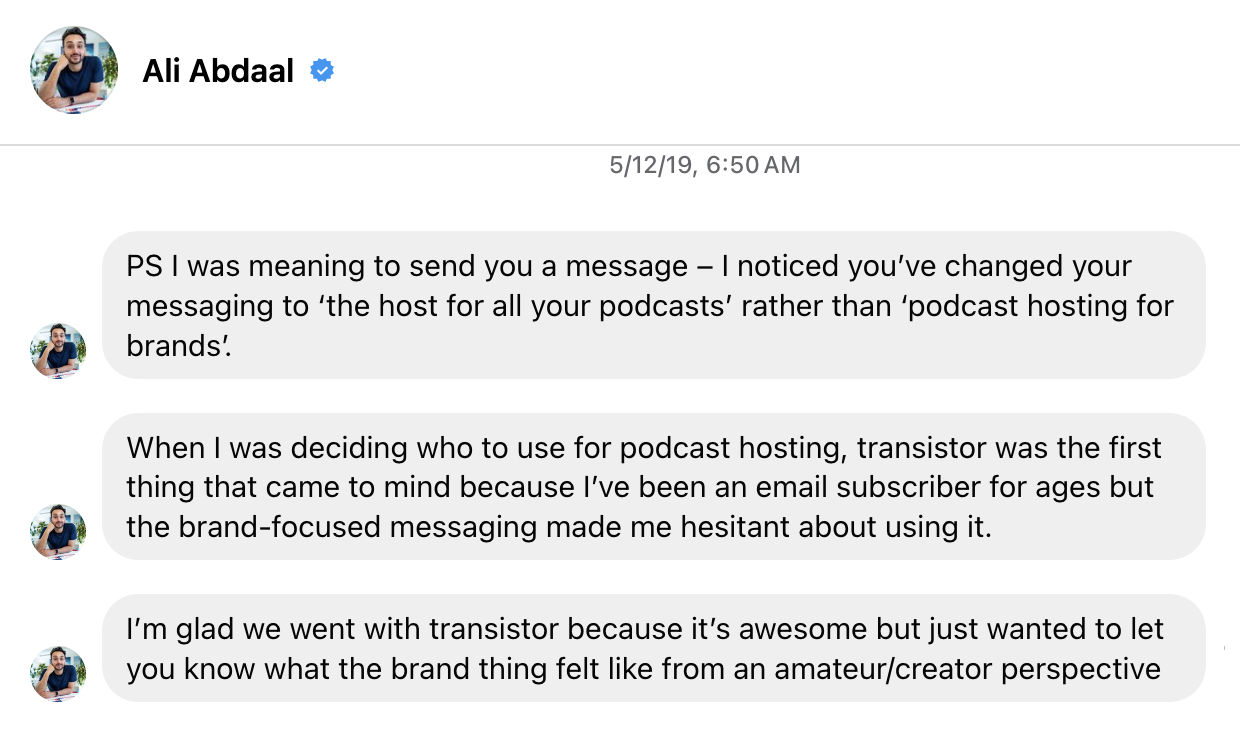

Then, I received a revealing DM from Ali Abdaal, a YouTuber who had signed up to do a podcast with his brother:

"When I was deciding who to use for podcast hosting," Ali said, "Transistor was the first thing that came to mind, but the brand-focused messaging made me hesitant."

His message concerned me: was our B2B emphasis scaring away potential customers?

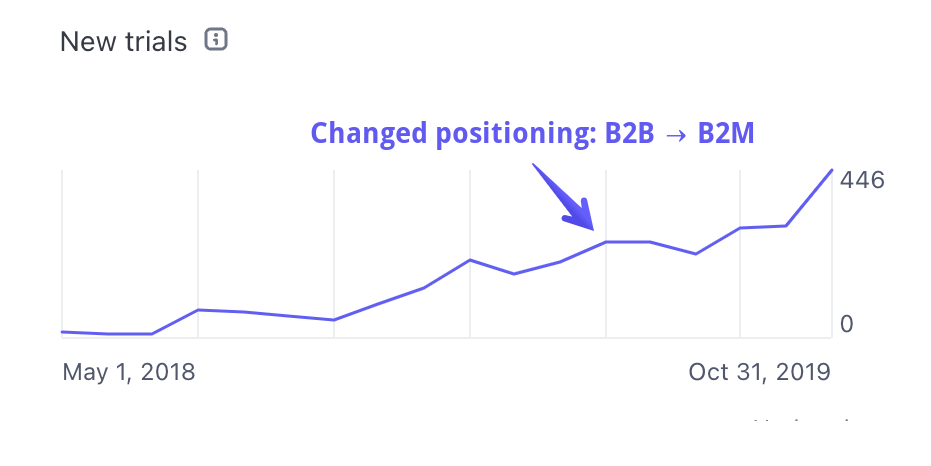

After considering Ali's feedback, we broadened our approach and adopted the more inclusive tagline "Your podcast's publishing platform."

The result? Our monthly trials doubled.

We've since seen strong signups from diverse customer types beyond our initial B2B focus.

We realized that hobbyists, prosumers, and businesses all wanted the same thing from a podcast host: an easy way to upload, publish, and distribute their podcasts to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, etc.

By exclusively targeting B2B, we had inadvertently excluded many potential Transistor customers!

Today, we serve over 33,000 users. I estimate our customer base as 30% hobbyists, 30% prosumers, 30% SMBs, and 10% enterprise companies, governments, and large non-profits.

Interestingly, our revenue breakdown challenges conventional wisdom. Some solopreneurs and smaller partnerships pay us significantly more than our enterprise customers! For us, a hobbyist's LTV can far exceed an SMB's.

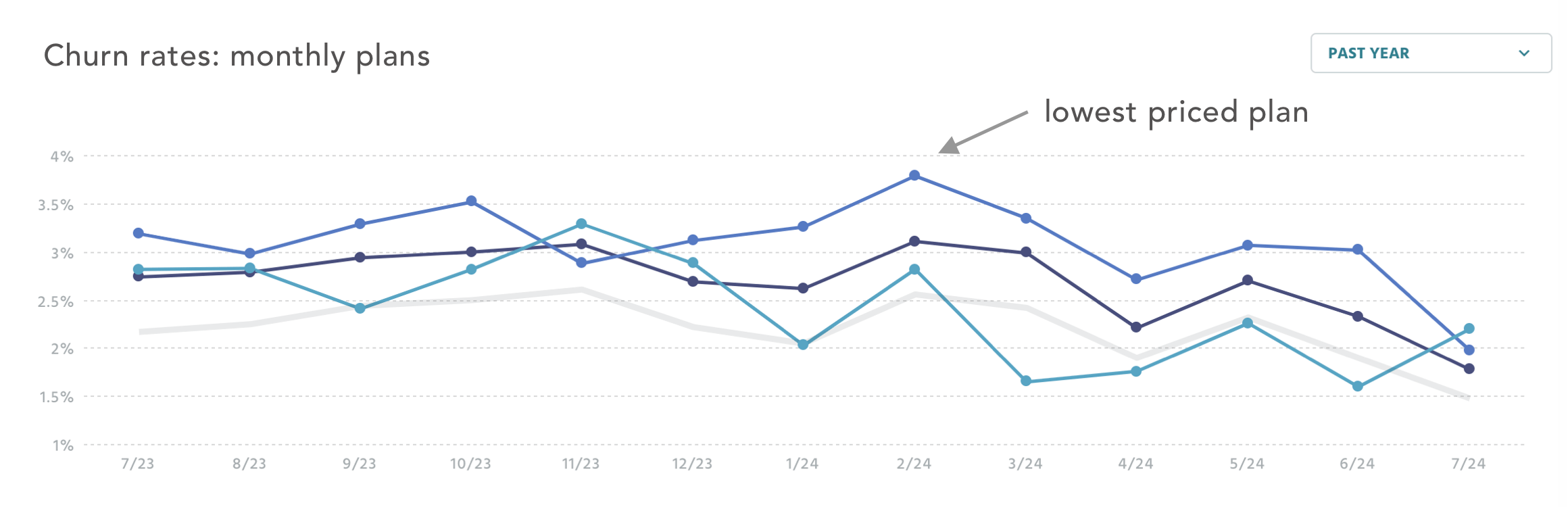

Despite a large B2C user base, the fears about serving these customers proved unfounded:

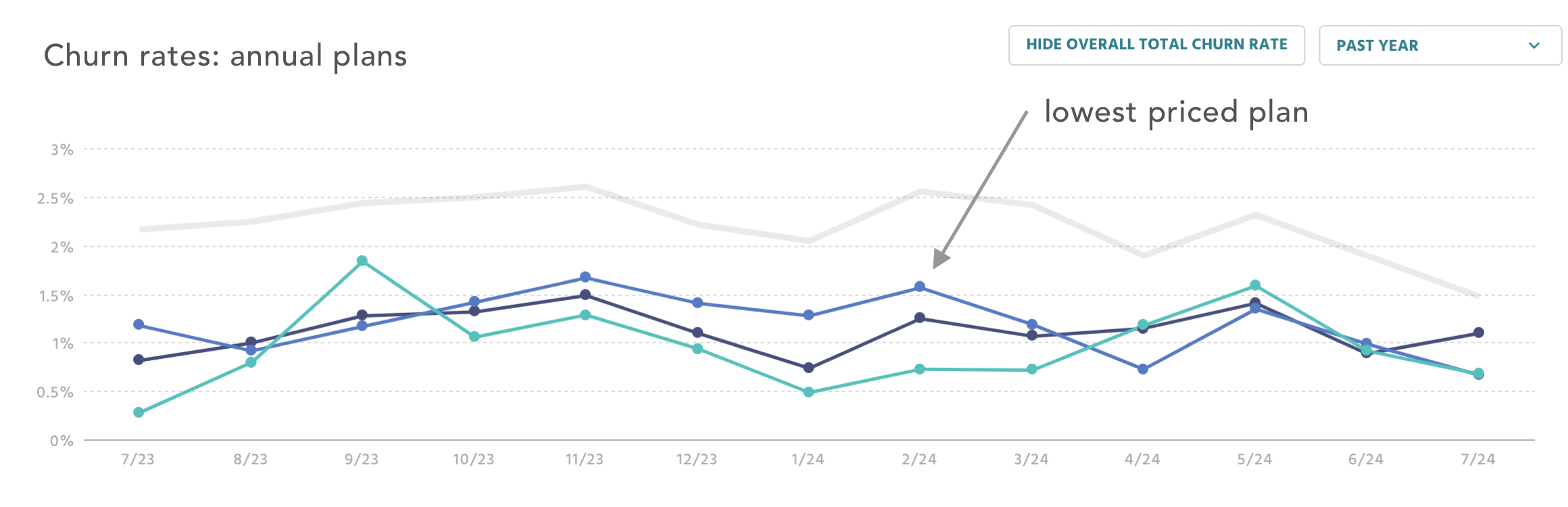

Churn is low (fluctuates between 1.9% - 2.6%)

Trial to paid conversion rate is 70-80%

Customer support levels are manageable (and we offer live chat)

In fact, churn rates for our lowest-priced plan don't significantly differ from our highest-priced plans. For annual subscriptions, the churn rate for the $190/year plan nearly matches that of higher-priced tiers.

We're not alone in this approach. MailChimp, Carrd, Fathom Analytics, Laravel Forge, and Tailwind UI all cater to a diverse range of customers, from individual consumers to enterprises.

With SaaS, what distinguishes the B2B approach from B2C?

The common advice from startup gurus is: "If you're starting a SaaS, focus on B2B, not B2C."

For centuries, meaningful distinctions have existed between how businesses serve consumers (B2C) and how they serve businesses (B2B). The idea is that there are meaningful differences in how one targets, sells to, acquires, and serves a consumer vs a business. But what about now?

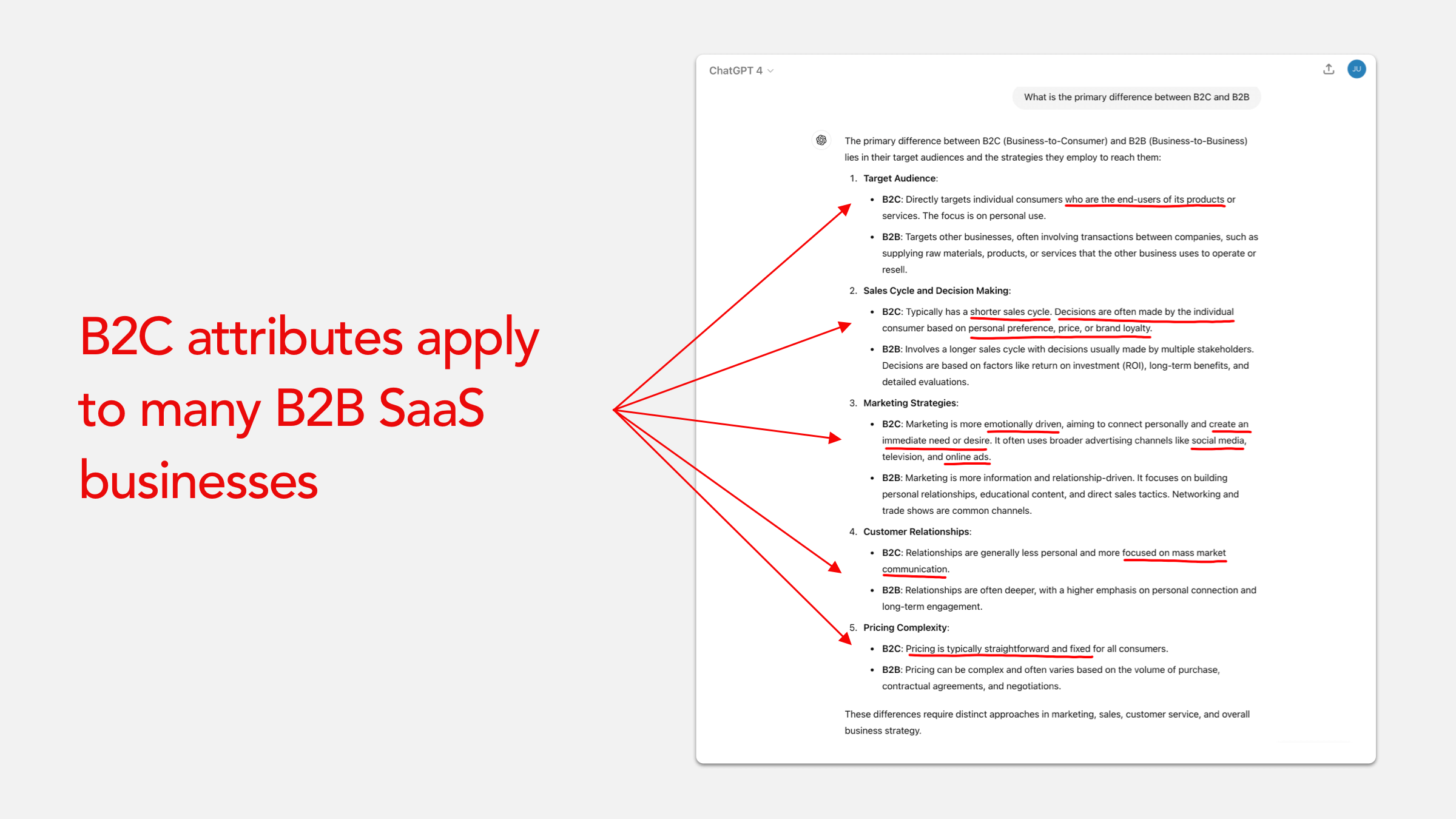

When you ask ChatGPT to list the attributes of each approach, many of the characteristics of B2C can also apply to B2B SaaS.

Surveying these attributes, I come to the following conclusions:

The "B2B" term is too expansive to be useful. When we say "B2B," are we equating a solopreneur using Trello to a Fortune 500 company spending $30k/year on Jira? Are we lumping indie creators spending $10/month with the government agency spending $1 million/year? There's a spectrum of "business" customers.

The rise of prosumers, solopreneurs, and "very small businesses" is significant. Today, anyone with a laptop and internet connection can start a business. There are many of them: freelancers, indie hackers, digital nomads, solopreneurs, tiny teams, creators, and influencers. These folks are technically "B2B" but act more like consumers when purchasing.

The line between B2C and B2B is blurring in SaaS. Quick decisions, single decision-makers, and transparent pricing aren't just B2C traits anymore. Many B2B customers (even in the enterprise!) buy software this way.

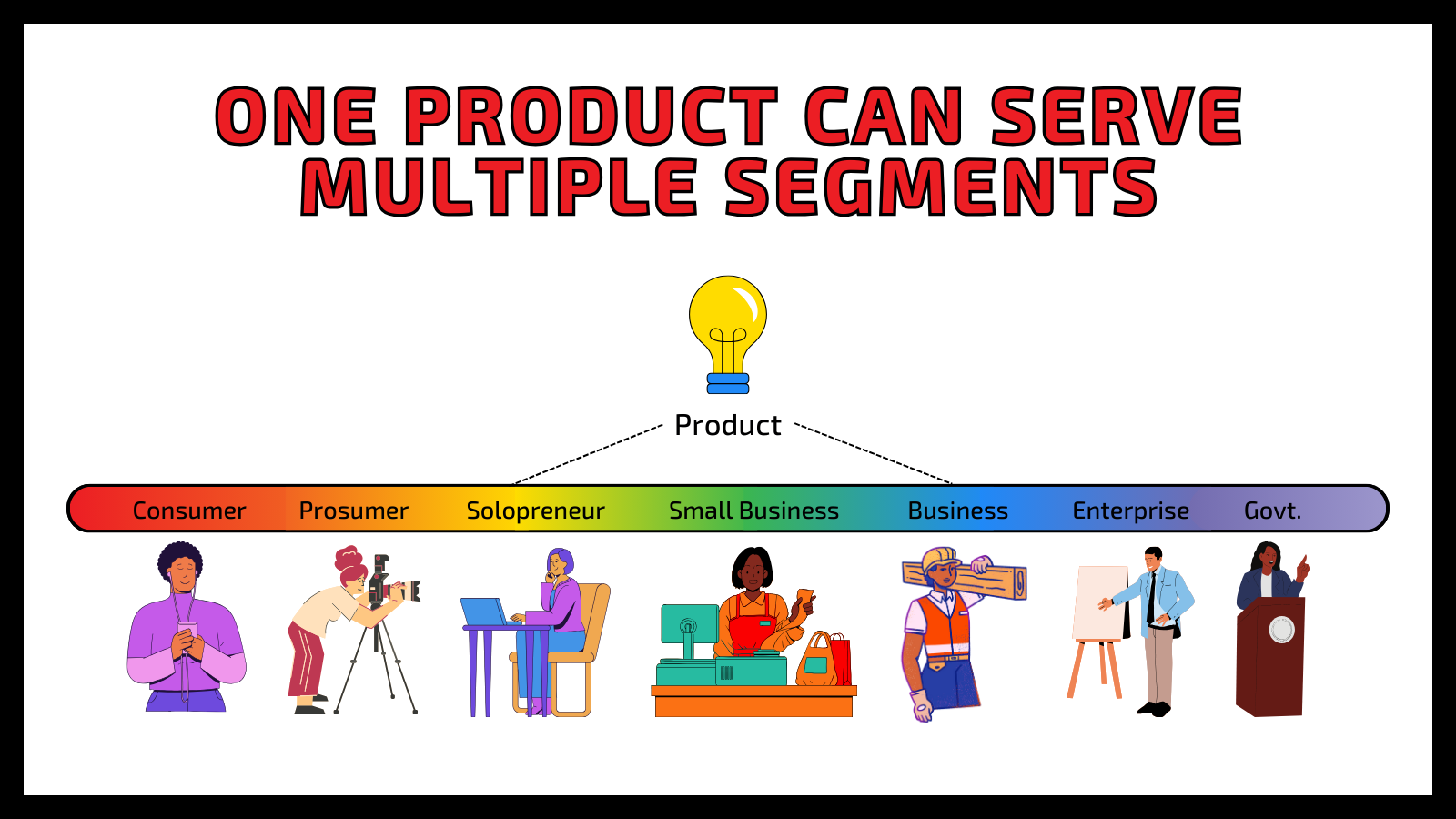

Today, you can serve multiple types of customers with the same product. It's possible to serve B2C and B2B customers simultaneously because their behavior and expectations are increasingly similar.

Beyond B2C and B2B: The Full Spectrum of SaaS Customers

The traditional B2C/B2B categories fail to capture the diverse range of SaaS customers. In reality, we're dealing with a much broader continuum:

Consumers

Prosumers

Solopreneurs

SMBs

Large businesses

Enterprises

Governments

Non-Profits

Your SaaS might cater to just one of these segments or serve several simultaneously. Let's break down each type.

Business-to-Consumer (B2C)

B2C describes businesses that sell products or services directly to individual consumers for personal use. This encompasses a broad scope, from casual, low-cost purchases to high-value products catering to passionate hobbyists and enthusiasts.

I'll also say that I don't think "B2C SaaS is always a bad idea." It depends on the volume of interest, willingness to pay, and the cost to produce the product and serve the customer.

For example, there's a difference between someone paying $0.99 for a weather app and a skier paying $32/year on OpenSnow. In this case, OpenSnow has built a good business serving these "high-value B2C hobbyists" because skiers spend thousands/per year on equipment and lift tickets, and $32 seems affordable.

A "passionate hobbyist consumer" might be a worthwhile market to target (assuming the market fundamentals are solid).

Business-to-Prosumer (B2P)

Wikipedia defines a prosumer as "a serious, enthusiastic consumer: not professional (earning money), but of similar interest and skills to a (generally lower level) professional, or aspiring to such. The target market of prosumer equipment."

However, the term has also evolved to mean "individuals who straddle the line between consumers and producers. They're often incentivized to invest in products and services with the dream of earning a side income."

For me, the key element that distinguishes a Prosumer from a consumer is that they view their purchases as investments rather than mere expenses. They hope their pursuits will generate income someday, which fuels their desire to invest in tools, equipment, courses, and resources.

YouTubers, DJs, TikTokers, photographers, musicians, artists, podcasters, and indie game developers could all be Prosumers.

Business-to-Solopreneur (B2Solopreneur)

Solopreneurs often represent the next evolution of a prosumer: when their passion starts generating income.

Picture this journey:

An EDM fan gets interested in DJing

They invest in equipment and hone their skills

They start playing free gigs to gain experience

Eventually, they graduate to paid gigs like weekend weddings

Finally, they might land a full-time gig at a club

The solopreneur category is incredibly diverse, especially in terms of revenue. It includes:

YouTubers who are just starting to monetize, perhaps earning $50 a month

Freelance designers making a comfortable living

Indie hackers like Pieter Levels, who earns millions from multiple streams of income

Solopreneurs can be lucrative customers. For example, Pieter Levels pays Replicate $25,000 monthly to use their AI API.

Business-to-Small-Medium-Business (B2SMB)

In my opinion, this category is too broad and encompasses sub-categories with meaningful differences that should be broken down further:

Very small businesses: teams of 2-10. These can be small design firms, software companies, retail shops, law offices, or partnerships. It's estimated that about 80% or more of businesses in North America have fewer than ten employees.

Small business: companies with 11-50 employees.

Medium businesses: companies with 50-500 employees.

Large businesses: companies with 500-1,000 employees.

In some product categories, you can reach some or all of these customers with the same go-to-market strategy. Other categories (like CRM software for large businesses) might require a targeted approach.

Business-to-Enterprise (B2E)

"Enterprise customers" are typically defined as having 1,000 or more employees.

But it's not just about size - it's also about the complexity of needs and buying processes. These organizations have dedicated procurement teams, multi-layered approval processes, and large budgets.

If you're targeting an Enterprise sales model, you'll need to play their game: hire salespeople, conform to a long sales cycle, and negotiate every contract.

However, if you're targeting multiple customer types with the same product, you can get Enterprise users to sign up the same way a consumer would: self-serve with a credit card.

Enter "B2Many"

Startups like Canva, ChatGPT, Trello, Slack, and Notion don't just serve one segment (B2C, B2SMB, B2Non-profit). Instead, they serve multiple customer types with a single, versatile product.

I call this approach "B2M" or "B2Many."

Canva perhaps best exemplifies the B2M approach. It started by targeting consumers. However, those same consumers quickly started bringing Canva into their office jobs, retail shops, freelance gigs, government agencies, and enterprise businesses.

Today, Canva has 185 million users and $2.3 billion in ARR. Their product serves everyone from individual hobbyists to Fortune 500 companies. This is the kind of scale that B2M can create.

What is B2Many?

B2M upends the old B2C/B2B convention and acknowledges that a single product can serve multiple customer types: consumers, prosumers, businesses, enterprises, governments, and non-profits.

The B2M approach mirrors what we've seen with the BYOD, Consumerization of IT, and Shadow IT movements that upended the enterprise market. The iPhone is a great B2C device that has also replaced BlackBerry in the B2B context.

B2C, B2Prosumer, B2SMB, B2B, and B2E users want the same thing: a simple, user-friendly product that gets the job done.

The Gmail example

Another example is Gmail: it's a popular product that serves a spectrum of customers.

Consumers get access to the same functionality (for free) that enterprise customers pay for (email, Documents, Sheets, and Drive).

The UX for a consumer and an enterprise employee is essentially the same. The only difference is that enterprise customers get administrative tools layered on top.

For Gmail, consumer awareness drove top-of-the-funnel demand for their business and enterprise products. Consumers who used the GSuite at home gradually recommended that IT adopt it at work.

Benefits of the B2Many approach

The Gmail example shows how B2Many taps into the power of bottom-up adoption.

This happened for us at Transistor as well: many customers started using us for a personal podcast and later recommended us to their boss. This is how we acquired many of our enterprise, government, and non-profit customers.

By targeting multiple segments with a single product, companies can:

Diversify revenue streams: reduce your dependency on any single market and smooth out seasonal fluctuations that might affect certain segments.

Achieve faster growth through word-of-mouth across segments: consumers and folks with side projects become advocates for your product when they go to the office.

Increase the lifetime value of customers: users "grow" with your product (consumer, to prosumer, to SMB, to enterprise).

In our experience, having a broad user base also helps us improve usability. We know our product is used by all sorts of folks in different contexts, so our UX has to be simple and clear.

Challenges of the B2Many approach

Serving multiple segments isn't without challenges:

You have to balance features for different user types.

Marketing to diverse audiences can be challenging, especially when creating headlines and campaigns that aren't overly generic.

Pricing can also be tricky. You need to offer a lower entry price for consumers and prosumers but have a pricing model that can scale up to enterprise customers.

Addressing the critics

As I've shared these ideas with others, here are some critiques I hear.

"I don't buy it. I think everything right of Prosumer is just B2B."

The line between "consumer" and "small business" is blurry. Is a YouTuber a consumer or an "aspirational business owner?" What about a freelance writer or a hobby podcaster? The prosumer movement is changing traditional definitions: users often start as consumers and evolve into businesses over time.

Also, the traditional B2B attributes (long sales cycles, demos, etc.) don't apply to modern, self-serve software products. The buying process looks more like B2C: individual buyers with a credit card decide what to buy based on personal preference, brand, friendship groups, etc.

Products like Canva, ChatGPT, and MailChimp succeeded by breaking out of the traditional B2B mold and serving a broader spectrum of users (consumers up to enterprise users) with a single, versatile product.

"Aren't Mailchimp and Slack B2B products? Do consumers use those products?"

When Mailchimp switched to freemium in 2009, it enabled consumers to start using them for a variety of reasons:

Personal Event Invitations (weddings, etc): many people use MailChimp to manage invites, updates, and follow-ups for personal events like weddings, family reunions, or birthday parties.

Community Groups and Clubs: Members of book clubs, running clubs, or local sports teams use MailChimp to distribute newsletters, coordinate events, and share updates about group activities.

Personal newsletters: for years, I used MailChimp to send my family's annual Christmas newsletter update.

Slack experienced a similar effect. This year, the NYT reported couples using Slack "to maintain their relationship." In 2015, Fast Company wrote:

"Users have appropriated the platform for extracurricular use cases like staying in touch with groups of friends, backchanneling at events, and creating chat rooms around interests like books or entrepreneurship–or dating."

"You're ignoring meaningful differences between B2C and B2B. For example, individuals and smaller companies are usually OK with paying by card after a free trial. Larger companies need invoices to pay upfront."

I understand these distinctions can exist, but they're not present in every product category.

My company, Transistor, offers podcast hosting. Our customers include hobbyists, prosumers, SMBs, big enterprise customers, and the federal government.

Sure, we've had enterprise companies and governments request SOC2, ISO, security reviews, payment by invoice, and dedicated customer support. In every case, we've pushed back and said:

Our product is a self-serve subscription

Payment is by credit card (we don't do invoice payments)

You have to sign our standard terms of use (the one exception is we have separate standard terms for government agencies)

You can use our standard customer support channels (live chat, email)

We don't do ad-hoc security questionnaires. We have a standard set of security details. If something's not covered there, they can contact our live support.

In most cases, big customers are willing to sign up the same way as individual customers. They get the same product for the same price, and they upgrade if they need more features (monthly downloads, more private podcast subscribers).

Notably, the customers who pay us the most are not necessarily the biggest companies! Many 2-10-person companies pay us significantly more than our enterprise customers. Folks pay for the value they receive (regardless of how large their headcount is).

For your next startup, consider moving beyond B2C/B2B

Founders shouldn't preclude themselves from exploring any target customer, whether B2C, B2Prosumer, B2B, or otherwise. If you have the insight to sell snow forecasts to skiers, you should probably pursue that opportunity.

You don't need to pigeonhole yourself into a single category. At Transistor, we earn revenue from multiple customer types: hobbyists, prosumers, SMBs, and bigger organizations.

Let me be clear: I'm not advocating that every SaaS founder should pursue a B2M strategy. The right approach depends entirely on your product and market. Sometimes, focusing on a specific B2B segment is exactly what you should do.

Instead, I'm trying to communicate two ideas:

The B2C vs. B2B narrative is too simplistic to be useful. It's time we recognized that the attributes often ascribed to B2C—like shorter sales cycles, single decision-makers, and price sensitivity—frequently apply to B2B segments, especially when referring to prosumers, creators, solopreneurs, and SMBs.

In the right product category, serving multiple customer types is an incredible business model. B2M has enabled my team to build a versatile, 7-figure business that serves a spectrum of users. We've done this without experiencing most of the downsides often prescribed to B2C: high churn, high support costs, etc.

With the rise of product-led growth and the consumerization of enterprise software, we're witnessing the blurring of B2C and B2B boundaries. MailChimp's $12 billion sale to Intuit, the largest acquisition of a bootstrapped startup, is a testament to the potential of this approach.

Rather than limiting yourself to a narrow definition of "business" or "consumer," consider how your SaaS might simultaneously serve multiple types of customers.

Cheers,

Justin Jackson

Connect with me on:

💼 LinkedIn

🐘 Mastodon

🧵 Threads

🐦 Twitter

Thanks to Kyle Fox for coming up with the "B2Many" label. I originally called this concept "B2Spectrum."