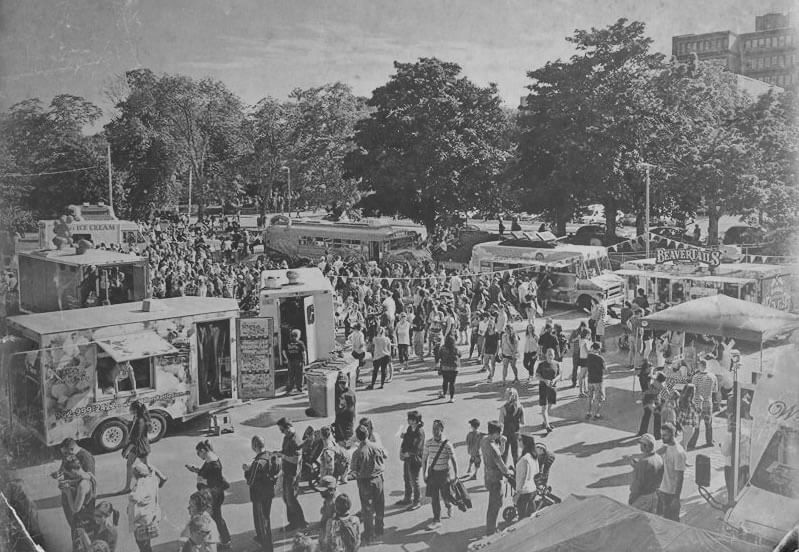

Selling stuff on a busy beach

It's unlikely you'll convince someone to buy something where there wasn't already existing demand.

Markets move towards desired solutions naturally; like folks lining up for ice cream on a hot summer's day.

Hat tip to Jason Cohen for originally coming up with this metaphor:

"The “long tail” can sound appealing, but it sure is easy to sell vanilla ice cream at the beach even when you’re right next to another ice cream stand."

If you set up an ice cream stand on a busy beach, you'll easily attract a crowd.You won't need to work (too hard) to sell ice cream, because the demand is already there. In fact, someone else could set up an ice cream stand on the other end of the beach, and you'd still do fine. On a hot day, there's a ton of demand for ice cream.

"The point of the metaphor is to say: don’t do demand-generation. Rather go where demand is built-in; then, it's easier (even when there are competitors)." – Jason Cohen

Now, think about what it'd be like selling ice cream on the beach during the winter.If you worked really hard and did a bunch of advertising, maybe you'd get a few sales, but not many.It's hard to push a product that the market doesn't want!

An example from my life: snowboard retail

I've experienced this dichotomy personally.In the past, I've run businesses where I was pushing really hard to get sales. It always felt like a grind, like moving a rock up a hill.

In almost every case, I was trying to create a product for a market category, or a specific niche within that category, where there wasn't much momentum.

For example, in my early 20s, I started a snowboard shop, right when that category was crumbling. Plus: my niche (the tri-cities area I lived in) didn't contain enough potential customers to make the business work.

Customers were already in motion. In the early 2000s, internet shopping was becoming a thing. Kids were discovering they could get the same product, for less, online.

In retail, you can feel it when the market wants your product (it flies off the shelves). In the early days, kids would search everywhere for a limited edition skateboard deck. They'd call you from three towns over. They'd drive an hour to come pick it up.

But, you also feel it when the market doesn't want what you're selling. We had some product that would stay on the shelves forever. No matter how much you reduced the price, you couldn't change the customer's attitude towards it.

You learn quickly that you can't fabricate demand (at least not easily). You're either in a market that's hungry for what you're selling, or you're not.

Why do some companies find it easier to get traction?

In his excellent series on Product-Market Fit, Brian Balfour observes:

There are certain companies where growth seems to come easily, like guiding a boulder downhill. These companies grow despite having organizational chaos, not executing the “best” growth practices, and missing low hanging fruit. In other companies, growth feels much harder. It feels like pushing a boulder uphill. Despite executing the best growth practices, picking the low hanging fruit, and having a great team, they struggle to grow.

He notes that the answer isn't to simply "build a great product." Instead, he recommends that you start with the market.

When you target a solid market (with good distribution channels) and give them a product that they're hungry for, you don't have to do much pushing or pulling.

Why it's better to choose a growing market

In most cases, I think bootstrappers should go after an existing market category that's displaying good upwards momentum.

For example, Jason started a WordPress hosting company in 2010. By that time, website hosting (and WordPress hosting) was already a large, commoditized category.

But, it was still growing. On Twitter, Jason Cohen says that choosing that market was crucial:

"Bootstrapping during those first 18 months would not have worked out so well, had we picked any other CMS than WordPress. The 'large and growing market' was critical to our success."

Many of us (me included) have a propensity to want to invent a new category. The problem is, as bootstrappers, we don’t have enough time, money, and energy to educate the customer about something new.

April Dunford, the author of Obviously Awesome, concurs here:

If you do a good job picking your market category then you don't have to list every single feature, because it's assumed. I know what a CRM is! But, if you did a lousy job of picking your market category, you've got trouble. Now you're going to have to spend a significant amount of your sales and marketing energy [describing what you've built]. It's way easier to sell in an existing category (vs making a new one).

(BTW, that's from this podcast interview. It's fantastic)

Ignore Steve Jobs, Henry Ford, Walt Disney, and Thomas Edison

Invariably, when I start describing these ideas, I'll hear some variation of: "But Steve Jobs built a product we didn't even know we needed!"

First, yes, it's possible for a special type of innovator to create a whole new category (or define it).

But even innovators like Steve Jobs are generally responding to a market category's existing momentum, and seeing opportunities within it:

- Cell phones. (existing category)

- "Everyone has a cell phone." (momentum)

- "But nobody likes it." (opportunity)

Are you struggling to get product traction?

If you're struggling to gain traction, you likely have a problem in your:

- market category

- channels

- product

Your issue might be in one of these areas; or all three! But start by looking at your market. The market you target is the foundation; everything else gets built on top.

And, don't be scared to enter a big, established market! Seeing proven demand for a particular category should motivate you (not deter you).

Aside from WPengine, many bootstrapped companies have entered existing markets, and succeeded:

- ConvertKit. Nathan Barry started an email marketing company in 2013. By that time, MailChimp was an 800-pound gorilla! There were hundreds of other competitors as well, but Nathan managed to carve out a slice of the market.

- MeetEdgar. Laura Roeder built her social media scheduling tool in 2014; well after Buffer and Hootsuite had raised millions in venture capital.

- Beanstalk. Launched in 2007, Natalie and Chris Nagele "built Beanstalk to remove the hassle from hosting code and managing deployments." That market has huge competitors: GitHub, Bitbucket, GitLab, and Microsoft.

There are also newer bootstrapped startups doing the same thing:

- UserList. This newcomer spells it out on their homepage: "less complex than Intercom or Customer.io." They're also competing with veterans like Mixpanel.

- Transistor. My startup is in an old, commoditized category (podcast hosting), but it's growing.

- Fathom. My friends Paul Jarvis and Jack Ellis couldn't have picked a more challenging category: website analytics. Their competitors include Google Analytics and Mixpanel.

Learn to recognize when there's upward momentum in an existing category.

Cheers,

Justin Jackson

@mijustin

This post was originally published on August 13, 2019. It's been updated since then.