How many units can you sell?

If you're selling anything online, pay attention to these two variables:

- Unit economics: how profitable is one "unit" of your product or service? (one digital download, one month of MRR)

- Sales volume: how many units can you sell every month?

Case study: iTunes vs Spotify revenue

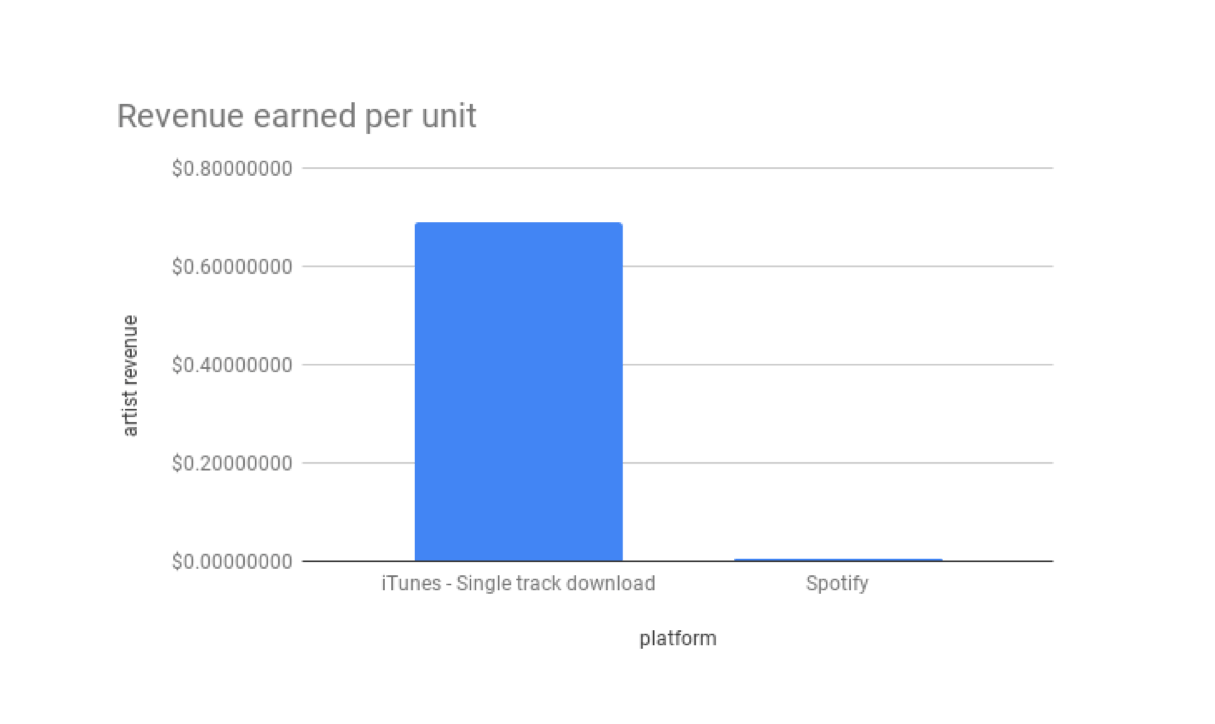

Unit economics

In the early 2000s, indie musicians could make pretty good money selling tracks on iTunes.

iTunes sold tracks for $0.99 and gave artists $0.69.

But by 2012, Spotify was grabbing significant market share (with 20 million total active users).

Unit economics worked differently on Spotify: they paid between $0.00331 and $0.00437 per stream.

Proft margin per unit had gone way down (a ~99% decrease).

This means the artist has to work harder (stream more units) in order to make the same revenue.

The band Pamplemoose experienced this very thing, as frontman Jack Conte explained to Guy Raz:

The transition to streaming was really hard. Our streaming revenue was a tiny fraction of our iTunes revenue. The volume [of streams] wasn't making up for it. And so, you know, the income started to evaporate.

The importance of sales volume

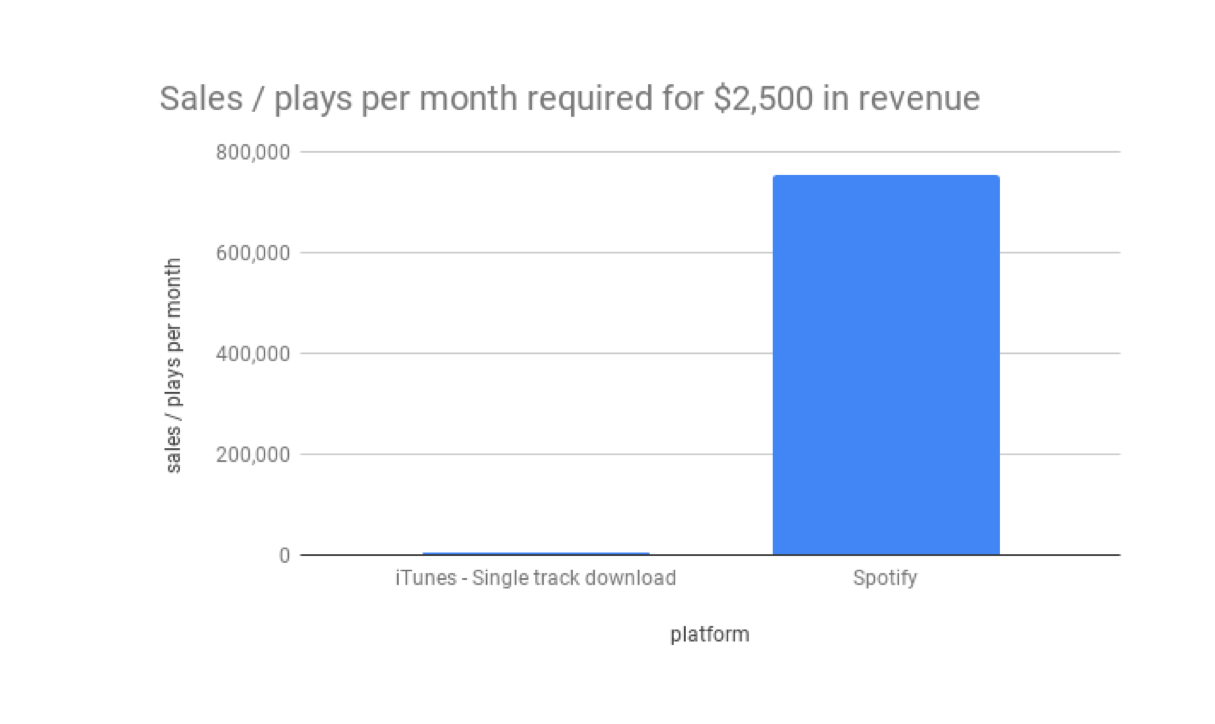

On iTunes, an artist needed to sell 3,623 tracks to earn $2,500 in a month.

But on Spotify, to earn the same amount, she needs to get 755,287 streams.

Because of poor unit economics, the volume required to hit baseline has gone WAY up.

How many customers can you reasonably reach?

Kevin Kelly introduced the idea of 1,000 true fans:

To be a successful creator, you don’t need millions. You need only thousands of true fans.

But the reality is making a living, especially as a musician, from just 1,000 people is difficult:

- On iTunes, to hit $2,500 per month in revenue, each of your fans would need to buy 3-4 new tracks per month.

- On Spotify, every fan would need to stream your music 755 times each month.

The truth is, most products (and most artists) have a natural "audience size."

If your potential market stays the same size, but your revenue per unit decreases, that's a recipe for trouble.

That's exactly what happened with Spotify and streaming, as artist Sharky Laguana explained to The Ringer:

"Something’s off when you can have the same audience size as you did 20 years ago but you’re making a fraction of the money."

SaaS founder and digital creators

So what does this mean for SaaS founders and creators selling digital products? You have two levers for earning more income:

- Volume: how badly do people want it?

- Profit: what are your price and costs?

How does this work if you wanted to, let's say, earn $10,000 per month?

Low-volume example

If you want to earn $10K / month, with 80% margins, but you typically only get 5 sales per month, your price is going to need to be $2,500 / unit.

High-volume example

For most SaaS (software as a service) and other digital products (courses, ebooks, downloadable templates) you'll need a high volume of sales.

If you want to make $10k / month, and your price is $25 (with 80% margins), you'll need 400 monthly sales.

Number of units sold x profit margin

Many aspiring creators and founders are eager to sell things online, but they don't stop to think about the numbers.

- How many units can I sell every month? What distribution channels do I have access to? Who owns those channels? How big is my audience? Have I made something that a lot of these people want?

- What price will people pay? This is generally determined by the market. If customers are used to paying $19/month, it's unlikely you'll be able to charge them $1,999/month.

- What are my costs per unit? What are your variable costs? How much does it cost you to deliver a unit? iTunes was willing to pay $0.69 per song, but now Spotify (the dominant distributor) only pays between $0.00331 and $0.00437 per stream.

Generally, you're either in a low-volume business (with a high price), or a high-volume business (with low prices).

And (again, generally):

- Most consulting/services businesses are low-volume/high-price

- Most SaaS/digital products businesses are high-volume/low-price

Make sure you know which business you're in, and charge accordingly!