The myth of the niche market

There's an old internet myth that goes like this:

- The web is big and has billions of users.

- Because the web is so big, even small niches have thousands of members.

- Therefore, you can target almost any niche and make money on the internet.

It's probably best exemplified in this old Merlin Mann quote from SXSW in 2009:

"Don’t have a blog about Star Wars, have a blog about Jawas. In fact, have a blog about that one Jawa who is only the scene for a minute. It’s going to be so much easier for you to dominate."

There is some wisdom in this: if you don't have a specific target in mind, it's difficult to build a unique position in the market.

But the idea that "the internet is big, and therefore, any niche will do" isn't true. There's more nuance to picking a market with strong demand than "the riches are in the niches."

1,000 true fans?

In 2008, Kevin Kelly wrote a groundbreaking essay that made a bold promise:

To be a successful creator, you don’t need millions. You need only thousands of true fans.

Kelly's spearheaded the idea that the internet makes almost any niche viable:

It's a theory that's full of optimism: "Every thing made can interest at least one person in a million — it’s a low bar."

His math works out in the sense that 1,000 people x $100 year = $100,000 (which for most people is a pretty good salary).

But in practice, the math is more complicated. Kevin Kelly later concedes:

"The trick is to practically find those fans, or more accurately, to have them find you."

Every product will need to attract some critical mass in order to succeed. Finding that "one person in a million," pitching them, and then convincing them to buy is harder than it seems!

Even with the internet, we still need to be able to reach groups of reasonable size at a reasonable cost; otherwise, it will cost you too much time and money to find them.

Plus, to earn revenue from a fan, you'll need to produce something that they want, and they're willing to pay for.

When choosing a market, there has to be some minimum bar for:

- the total number of potential customers

- how easy they are to reach

- the amount of demand they have for what you're going to make

- their willingness (and ability) to pay

In many markets, a pool of 7,000 potential customers won't be enough, especially if it costs a lot of time and money to acquire them.

How big of a market do you need to bootstrap a successful software business?

I've observed hundreds of independent entrepreneurs, at MicroConf, in MegaMaker, and in my role as an advisor.

Almost everyone who is consistently earning more than $10k / month (and certainly those who break $50k) targeted a growing product category, that was sufficiently large.

How large does it need to be? Here are some examples:

- There are over 5 million PHP developers in the world, so when Taylor Otwell launched Forge, he got 1,000 customers within a month.

- There are over 500,000 Shopify stores, so when Björn started making Shopify apps, he had a big pool of potential customers. Within six years, he was earning $275,000 in annual revenue.

- When Ruben Gamez saw that DocuSign had over 200 million users, he thought: "That's a big market." And so he launched Docsketch.

I think that asking "what's the smallest market I could serve?" is the wrong starting point.

Instead, look at the Total Addressable Market; the sum of the worldwide demand in a product category. Can you compete? Could you reasonably capture a percentage of that economic activity?

You can still target a niche within a larger market, but I wouldn't plan on capturing 100% of an already small market. As a bootstrapper, that's just not tenable.

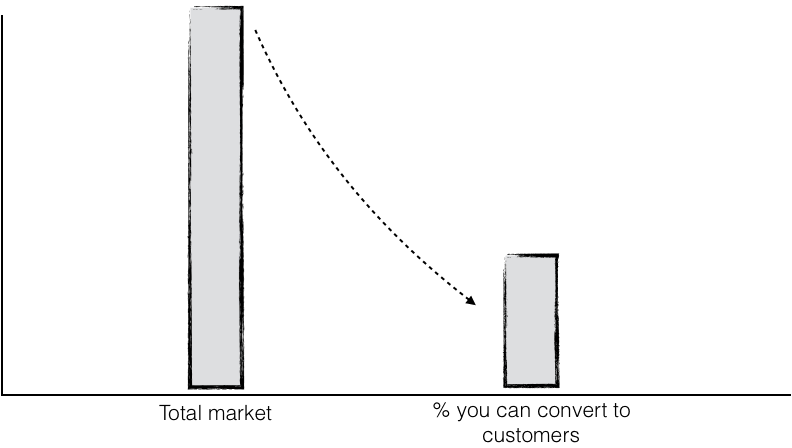

Typically, we start our funnels with "number of visitors," but in reality, the funnel looks like this:

If your total market is only 10,000 people, and you charge $100 per month, you might think: "I only need to find 100 customers to earn $10,000 a month."

But smaller markets have significant challenges:

- With a smaller market, your growth is generally slower.

- Finding channels that are reliable, repeatable, and affordable is difficult.

- There's a lower ceiling on your potential revenue.

It's not until you launch that you'll realize how hard it is to grow your business.

Many companies in small markets charge significantly more than $100 / month, but that can make growth and acquisition even slower (and might require salespeople).

Focusing on a smaller overall market could mean everything takes longer. When feedback loops are slower, it might take you longer to learn that your market is unsustainable.

Case study: Moraware

If you're thinking about launching a product for a small market, I highly recommend Techzing's interview with the founders of Moraware.

They make software for a niche group: countertop fabricators.

And they've been successful! Ted and Harry (the founders) have built up a nice business with Moraware. Launched in 2002, they grew to over 2,000 customers in 2019. They now employ eleven people (and they're hiring!).

But it wasn't easy getting there.

In the Techzing interview, Justin Vincent (the host) asks them about their journey. Here's an excerpt:

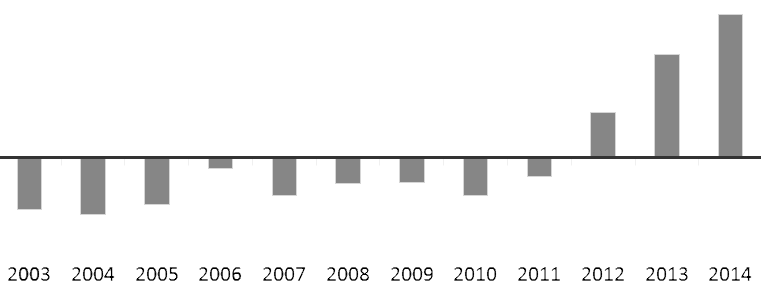

In a 2015 blog post, Ted notes that he and Harry both gave up six-figure salaries to start Moraware.

He goes on to say "this is what our profit chart would have looked like if Harry and I paid ourselves a market salary the whole time:"

Later in the interview, Justin asks them:

Again, what Ted and Harry achieved at Moraware is incredible: they've built a sustainable business that provides for eleven people and their families. It took them a long time to get here, but now they have a firm foundation that will serve them years into the future.

But if you're thinking of building a product for a small niche you should pay attention to their experience:

- Can you afford to spend ten years getting your company to scale?

- Are you willing to endure the slow grind?

- Are you OK with doing direct sales?

My experience

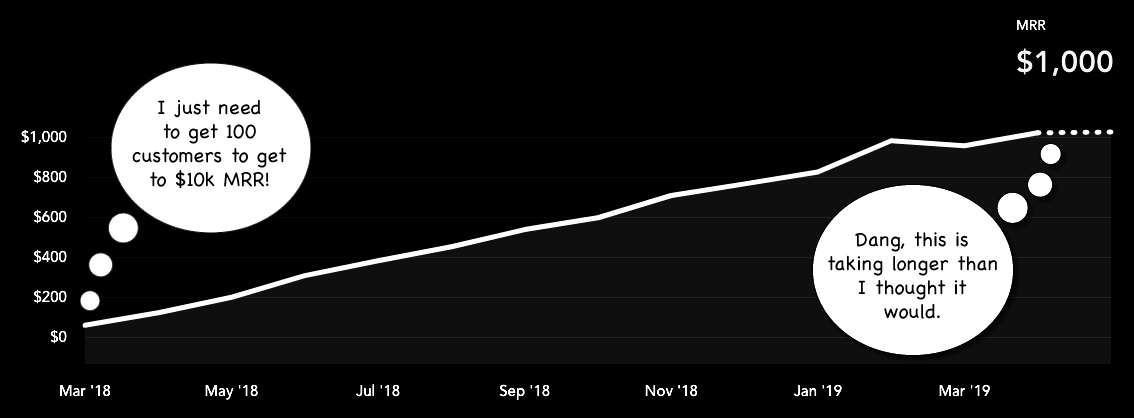

In 2018, I co-founded Transistor, a podcast hosting, and analytics platform.

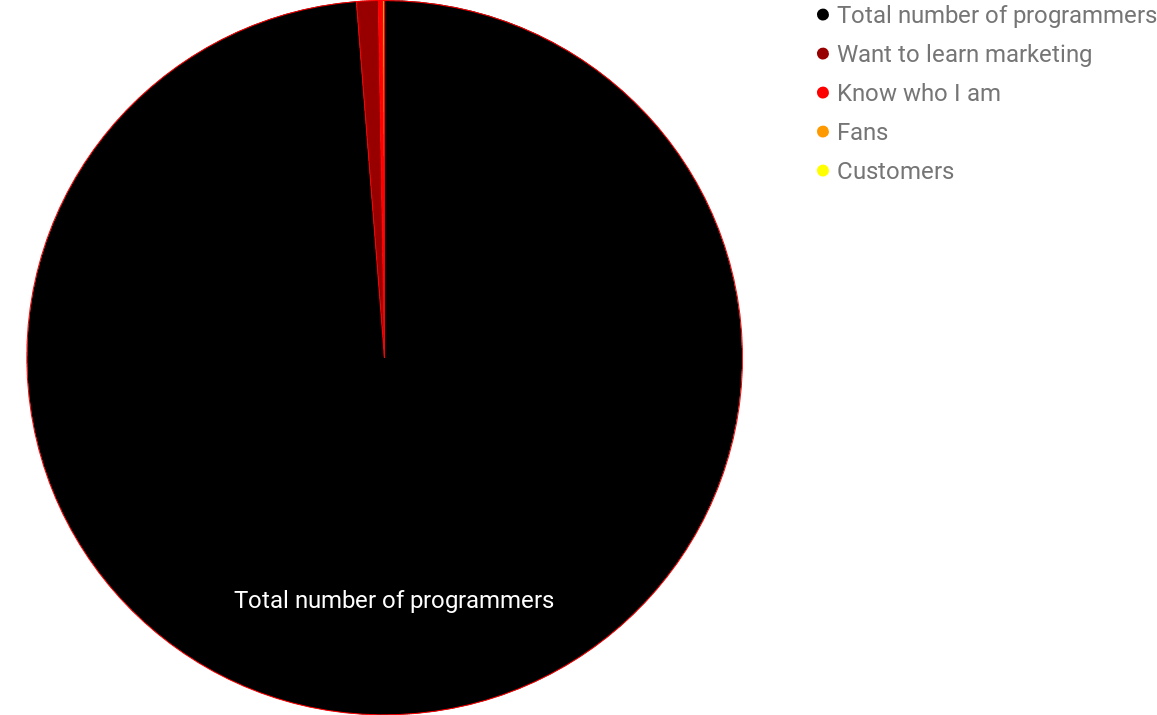

Before that, one of my most successful products was a course called Marketing for Developers. It targeted indie programmers who wanted to learn marketing skills.

On its face, this seems like a pretty good market. Developers spend tons of money on courses every year. But how many are in my niche? And more importantly: how many want to buy a course from me?

- Programmers worldwide – 26,400,000

- How many want to learn marketing – 264,000

- How many of them know who I am – 50,000

- How many of them are fans – 20,000

- How many people bought – 7,000

That big pool of 26.4 million gets whittled down pretty quick!

Between all my courses, I probably have about 7,000 customers (including customers from deal sites like AppSumo). Not bad! But if you're only selling one-time purchases, that's not sustainable.

As a contrast, my friend Wes Bos has probably made more than 7,000 sales in a single weekend selling to developers who want to learn JavaScript (a much larger niche).

Launching a SaaS

In addition to selling courses, I've worked for a variety of SaaS companies since 2008. It's been interesting to contrast those experiences to what's it's been like to launch Transistor.

Right now, the podcast market isn't huge, but it is growing: the number of podcasts in Apple's directory increased by 100,000 last year, to 700,000 total. And there's still, potentially, a lot of growth left. (YouTube, for example, as an estimated 36 million channels).

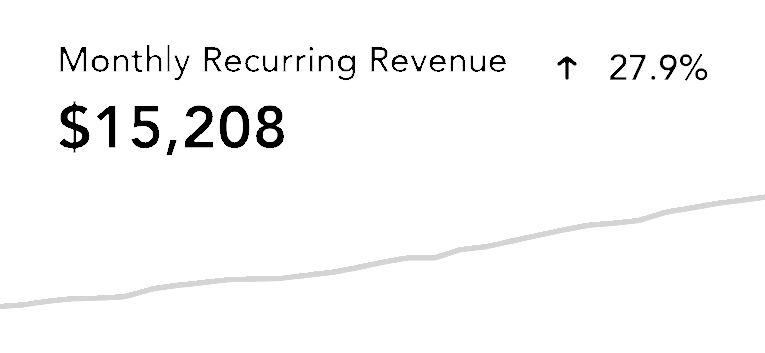

This past week, Transistor hit another revenue milestone: $15,000 in MRR.

Although Jon (my co-founder) and I can't pay ourselves full salaries yet, hitting that number, ten months after launch, feels significant.

We've been growing 20-30% per month. I don't know when that's going to end (every day I worry: "this is all going to disappear tomorrow"). But right now, the momentum in the podcasting market feels different than what I've experienced before.

My friend Jordan Gal says you need:

- Right product

- Right market

- At the right time

"You need all three, but if you don’t have the market right, everything is harder."

I believe that the market you target defines your company's capacity for success. Your timing and the product you launch will determine how much of that capacity you fulfil.

Gone fishing

There's a professional angler named Tony Bishop, who wrote a book called Fishing Even Smarter. It's full of good fishing advice:

Successful fishermen fish where fish are.

And when he expands on this further, his advice for anglers sounds like good advice for entrepreneurs too:

If your fishing rod is your product, and your lure is your marketing, the most important decision you make is still where you fish. Choose wisely!

Cheers,

Justin Jackson

@mijustin