Main Street fights back

In the past couple of weeks, I've focused my writing on the economic devastation caused by the coronavirus pandemic (Fight Amazon, We've Been Exposed). Last week I said:

Our society ain't right. And I don't want to just complain about it, I want us to do something about it. What can we do to help tilt the playing field, so it's fair for small businesses?

It's hard to imagine leveling the playing field when there are headlines like this:

- This week, the stimulus package that was supposed to help small businesses in the USA ran out of money. The New York Times reported that the stimulus didn't reach the small businesses that needed it most (restaurants, bars, and hotels). Ironically, some chain restaurants, like the Shake Shack, got millions.

- The Washington Post noted that "more than 80 percent of the benefits of a tax change tucked into the coronavirus relief package will go to those who earn more than $1 million annually."

- Meanwhile, megacorporations like Amazon are benefitting massively from society's current quarantine. The value of Jeff Bezos' wealth has increased by $24 billion since the beginning of the pandemic.

The Covid-19 outbreak hasn’t slowed Amazon down. Quite the opposite: even as other businesses have downsized or shuttered, Amazon has proved remarkably well-placed to capitalise on these new circumstances, with customers spending a reported $11,000) a second on its products and services.

Despite their surging sales, Amazon decided that now was a good time to cut their affiliate rates. Thousands of small businesses rely on Amazon commission checks for their livelihood, which affects folks like my friend Matt:

In past articles, numerous readers have tried to convince me that most small businesses would be better off to use Amazon's fulfillment and marketplace than pursue a viable alternative.

Now we can see the danger of letting Amazon control all the distribution. "It is in their interest," as Seth Godin says, "to pay workers and small businesses less."

How the system keeps us powerless

Most entrepreneurs have been sold a version of the American dream. The idea is that we can build our own little silos and create our own wealth. It's rugged individualism: each individual competes against each other, hoping to get a piece of the pie.

But it's a lie.

We're not competing for a piece of the pie, we're fighting for the crumbs.

Again, Seth Godin:

If you own the factory, you have something that workers don't have – which is the Means of Production. So if you can pit workers against each other, and they will bid down and down to get the job, you come out ahead.

These days, it's not so much owning the factory that gives you power; it's owning the Means of Distribution. This is Amazon's big strength. They have the:

- physical distribution: their warehouses, distribution centers, and logistics,

- software platform: their storefront, cloud architecture, search engine, and traffic.

Since 1994, Amazon has invested billions of investor money (and most of its profits) into creating the world's largest marketplace. They've become the platform where buyers and sellers do commerce.

However, the effect is the same: Amazon can "pit small businesses against each other." They're happy to keep us all occupied, battling against each other. And they'll continue to squeeze their merchants and workers, by paying them less and less, because they own "the platform where commerce happens."

How we fight back

When we are divided, Main Street businesses, solopreneurs, and bootstrappers will continue to scramble for crumbs while big corporations gobble up the pie.

Maybe what we need is a new wave of collaborative commerce.

A single unconnected node isn't as resilient as a diverse, interconnected, network. The internet gives indie entrepreneurs the infrastructure needed to generate the kind of network effects that can compete at scale with companies like Amazon.

Platforms that enable collaborative commerce

We've already seen this work with open source projects, like WordPress, Laravel, and Ruby on Rails.

- WordPress made publishing a blog, website, or online store accessible to everyone. The underlying software is free. Anybody can contribute to the software, and add-ons that make WordPress more powerful are abundant (and low cost). This means an independent site like Apartment Therapy, led by Maxwell Ryan, is empowered to use the same publishing platform as a giant media company like TIME Inc.

- Laravel and Ruby on Rails are programming frameworks that make it easier for small dev shops to have a big impact. These frameworks allow Jon Buda and I to run Transistor.fm as a two-person company, even though some of our competitors have teams of 100. They also level the playing field economically. Jon and I bootstrapped Transistor with our own money; Rails and Laravel help us to keep our development costs low even while we compete against startups with millions of dollars in funding.

In the world of physical products, websites like IndieBound and Bookshop are providing platforms that enable local book stores:

- IndieBound allows you to search a network of independent bookshops, so you can buy it locally instead of ordering it online.

- Bookshop takes a different approach. They sell books online but give local bookstores a cut of the revenue.

These are examples of using the internet for the common good.

Communities that enable collaborative commerce

Traditional professional associations, chambers of commerce, and unions have a few problems:

- Invariably, they become obsessed with increasing membership, because their administrators need the funds to pay their salaries.

- They're often inwardly focused, and aren't very innovative.

- Technically, grassroots members have a "vote," but in practice, the top leadership makes all the decisions.

But today, the internet has given us ways to collaborate that don't require a big organization to run.

Online communities that run on Slack, Discord, forums, Reddit, and GitHub have enabled groups of people to join together, and collaborate.

These online communities still require leadership, but require far fewer people to run.

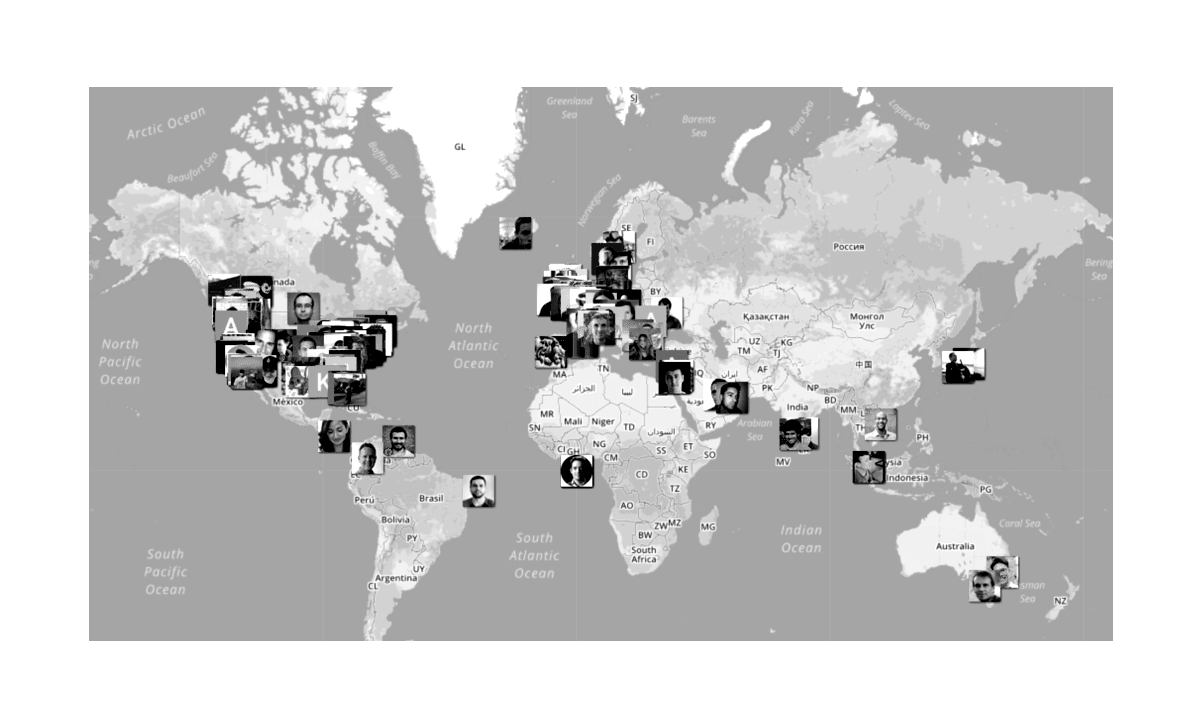

For example, MegaMaker, a private community for bootstrappers, has 606 members. It's moderated by myself, Jon Friesen, and Helen Ryles. And every day, indie entrepreneurs from around the world connect on our Slack and Discourse forums. We give each other technical and marketing help and connect folks to the resources they need.

Online communities give independent business owners more power. Instead of being alone, they have other people in their corner. Members benefit from each other's skills, resources, and networks. When you know you're a part of the group, it contributes to your sense of resilience: you're not alone.

My friend Andrew, who runs a local coffee shop, says that after the COVID-19 shutdown, a bunch of local restaurants and cafes started a Facebook group. Inside, they've been sharing resources, helping each other launch online stores, and providing emotional support.

Protocols that enable collaborative commerce

I'd be remiss if I didn't mention open internet protocols like email, RSS, and the web. Unlike closed communication systems owned by Facebook, Google, Twitter, or Apple, these platforms are free and accessible for anyone who wishes to use them.

What's next?

While there's evidence of collaborative commerce working in some online niches, it's still nascent. There's lots of opportunity for innovation.

Ideas for local shops

Main Street businesses need to form online networks that enable them to compete with Amazon on price, convenience, and brand. E-commerce platforms Shopify, Lightspeed, Woocommerce, and Square, could enable this collaboration. For example: when one local retailer doesn't have a product in-stock, why don't they suggest another local shop that does? There could even be a small commission for referring the sale.

Ideas for restaurants and coffee shops

For resilience in the future, restaurants are going to need to master takeout and delivery. The problem is those delivery startups like DoorDash, Grubhub, and Skip the Dishes take up to 25% of a restaurant's revenue. Restaurant profit margins are already razor-thin (3%-5% is normal). It's predatory for venture-backed delivery companies to be taking such a huge chunk of their order-value.

It's possible that a delivery co-op for restaurants would be cheaper than them using delivery services. They could all pool their resources and hire a single delivery driver who does everyone's orders. Or, they could offer to share deliveries: "I'll take Tuesdays, you take Wednesdays."

Ideas for online businesses

It feels like bootstrappers have a head start when it comes to building community. We have Indie Hackers, MicroConf, and tons of private Slack groups. Here are a few other ideas:

- Co-founder exchanges – what if two (non competing) startups decided to exchange co-founders for a week? A co-founder, or employee, switches places with someone at a similar-sized company. Each person can take their expertise and share it with the other startup.

- Collaborative hiring – I love Wildbit's "People First Jobs." They reached out to companies with similar values and created a job board that fits those ideals.

Petition your government

If it's true that stimulus money earmarked for small businesses didn't reach small businesses, we need to raise a ruckus.

For example, in Canada, the site savesmallbusiness.ca has attracted over 32,000 businesses who are campaigning the government together.

The internet allows us to form groups quickly and lobby the government with a collective voice.

Got more ideas?

I'd love to hear them. You can reach me on Twitter (@mijustin), or on my newsletter.

Cheers,

Justin Jackson