Ideas aren't cheap

John Doerr, a venture capitalist, is credited with saying:

"Ideas are easy. Execution is everything."

I disagree.

If ideas are so easy, why are most business ideas so bad?

Business ideas are observations paired with hunches.

Observation: "This is what people are doing. This is what people want. This is where the market is headed."

Hunch: "Here's a way we could help people to get the result they want (and do it better than what's currently available)."

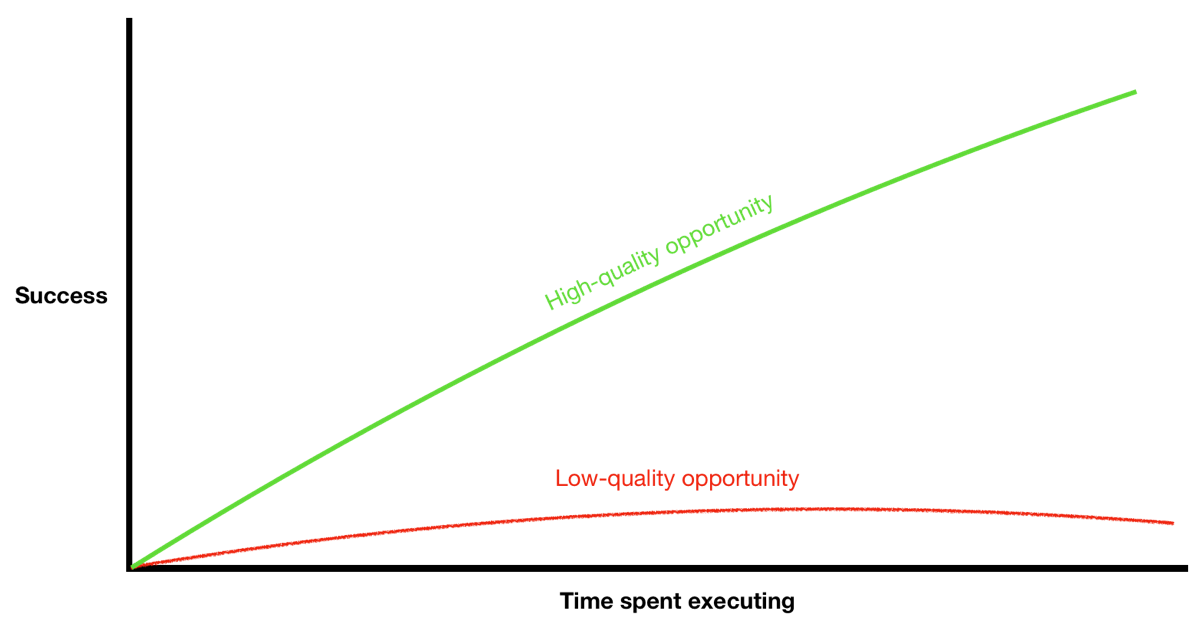

The results of your execution hinge on the strength of your original idea. How clear was your initial observation? How correct was your hunch?

Why your idea matters

The market you choose, and the idea that you focus on are the most critical business decisions you’ll make. They determine your trajectory.

Yes, how you execute is a part of that, but the idea itself sets your ceiling for success.

When an author says: "I have an idea for my next book," the success of that book largely depends on the concept they've chosen.The same is true in business.

The risk with overemphasizing "execution" is it deludes people into thinking that if they work hard enough, they can make any idea successful. It's just not true.

If you don't believe me, browse old listings on Product Hunt.You'll see page after page of beautifully executed products that never achieved meaningful traction.There have been thousands of ideas posted; most failed.

Many folks in tech are skilled at building software but struggle to build good software businesses.The difference is in the quality of their ideas.

We often compare ideas to seeds. But a bad seed can't grow into a plant; only a good seed can.

Got a bad idea? Don't spend lots of time fertilizing it, watering it, and trying to get it to grow. No! Throw it away.Focus on cultivating good ideas and helping them grow.

How to find good business ideas

I know talented makers who had to hunt for years before they found a good idea.

Identifying a good business opportunity is often the culmination of:

- the experiences you've had,

- the markets you've observed,

- the customers you've listened to,

- the experiments you've run.

Good ideas are not easy to find. And often, you have to wait for them to appear.

The problem is, most of us are impatient and want to execute as soon as possible, so we pick the first idea that comes to mind.

On Twitter, lots of folks told me: "But generating ideas is easy!"

Yes, coming up with low-quality ideas is easy. But being able to see the shape of a good opportunity is hard. (In the same way that noticing a wave from the beach is easy, but being able to identify a strong swell to surf is difficult).

"It's better to create a product for an audience/industry that you're already a part of because you know it well enough to have good hunches about what people need." – Corey Stone

Good business ideas come from making observations about how people act in the real world and then having an intuition for the best way to respond.

Copying someone else's ideas rarely works. As Jason Fried says:

Here’s the problem with copying: Copying skips understanding. Understanding is how you grow. You have to understand why something works or why something is how it is. When you copy it, you miss that.

If you're not generating very many good ideas, it's probably because:

- you haven't had enough experience in a given sector,

- you haven't learned to observe the way people behave,

- you haven't honed your instincts for recognizing the "pull" of a market.

Putting our ideas into action

For some folks, ideas are cheap and disposable. They want to have many ideas and explore them all simultaneously. But this isn’t efficient; you spread yourself too thin.

For others, validating an idea is a part of the "execution" step. They'll build an MVP, put it out into the market, and measure the response. If the reaction is bad, they'll try to iterate on the original idea (or pivot). The Lean Startup methodology very much influences that approach. My critique of the Lean Startup is that it still requires significant investment in building an MVP. You don't realize the idea is terrible until you've created something, put it out into the world, and gathered feedback on it.

Instead of those approaches, here's the framework I use now:

- I have many ideas (most of them are bad).

- As I evaluate ideas, some are worth exploring.

- I explore the shape of those ideas.

- I choose the idea that has the most potential (and best fits me).

- I research the idea more (usually by finding folks who are already paying for a similar tool or trying to accomplish a similar task).

- I research the market potential more (how many people are actively buying a similar product, how easy it is to reach them).

- I decide if it's an idea I want to commit to working on.

- I find the right partners (co-founders, contractors, advisors).

- If everything looks good, I start executing on the idea.

- If, after I start executing, I get the feeling that it's not going well, I pivot or quit.

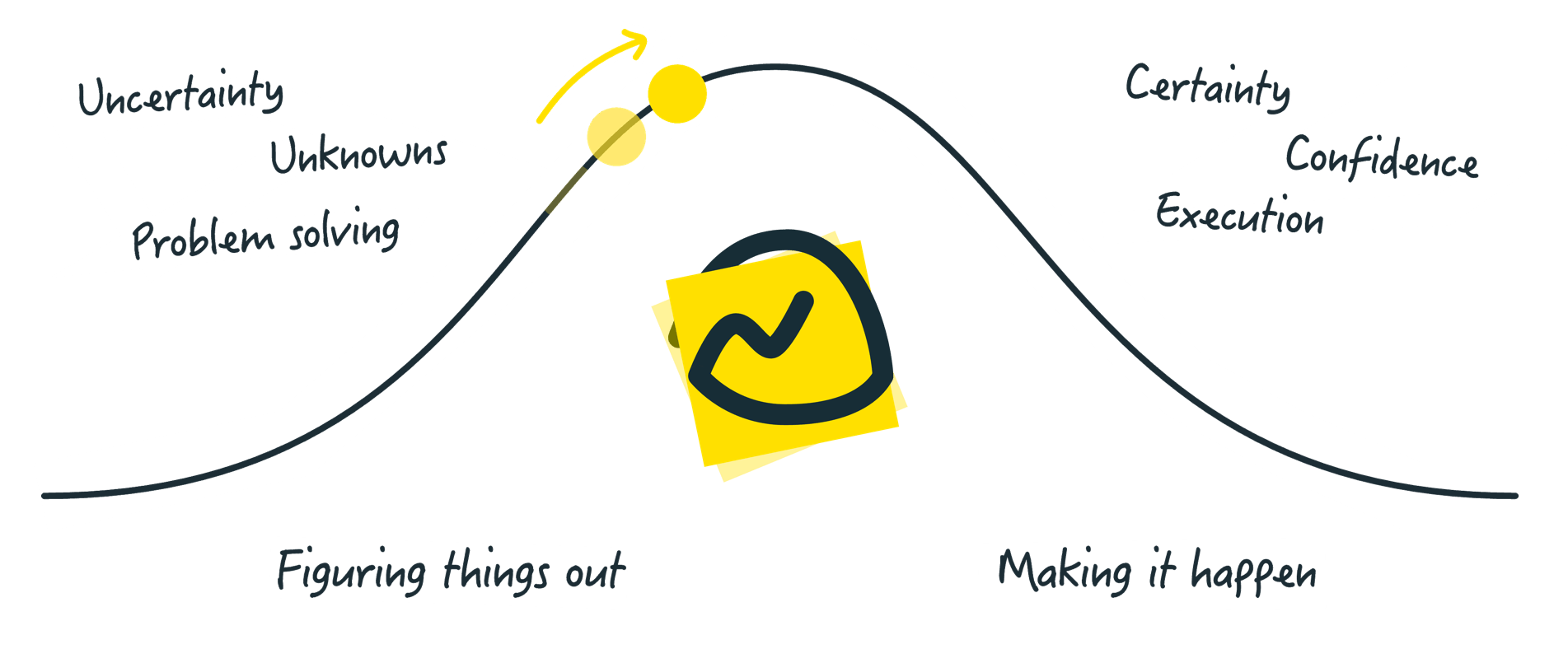

This framework is loosely based on the work that Ryan Singer and Basecamp are doing with their Shape Up process. At the beginning of a project, there is lots of uncertainty. So before they even consider an idea, they shape it first. They'll brainstorm several ideas, and then bring those ideas to a "betting table." Then they'll ask: "Which of these ideas do we have the biggest desire to pursue?" After they've answered most of their unknowns, they'll start executing. Their Hill Chart concept best illustrates this:

Execution means "to put a concept into action." If you were writing an essay for school, you would want to make sure that the idea you'd chosen was solid. In a brainstorming session, you might generate many ideas; but it's the strength of the concept you choose that will carry your paper.

Work on ideas that matter

To me, a good idea occurs when you pair an insight into a market with a hunch about how you should respond.

And, as DHH says, you should "work on your best idea:"

Why would you want to pour so much of yourself into anything less than your best idea? Other ideas might seem more achievable or convenient, but if your heart and mind is elsewhere it’s all for naught.

And remember, "your best idea" doesn't need to mean a concept that's original or novel.

DHH and Jason Fried built project management software. But it ended up being "a good idea," because their observations and hunches turned into highly-opinionated software that people loved.

Jon and I had been a part of podcasting since 2012. We'd been swimming in those waters, building (and using) different solutions for podcasters. Then, we observed the rising interest in podcasts from businesses and media companies. And we decided to respond with Transistor.fm. Transistor is our hunch about the kind of hosting platform podcasters want to use.

A "podcast hosting platform" isn't a unique idea. But it turned out to be a good concept to start in 2018. Our observation of the market, paired with our product instincts, has turned into a profitable business.

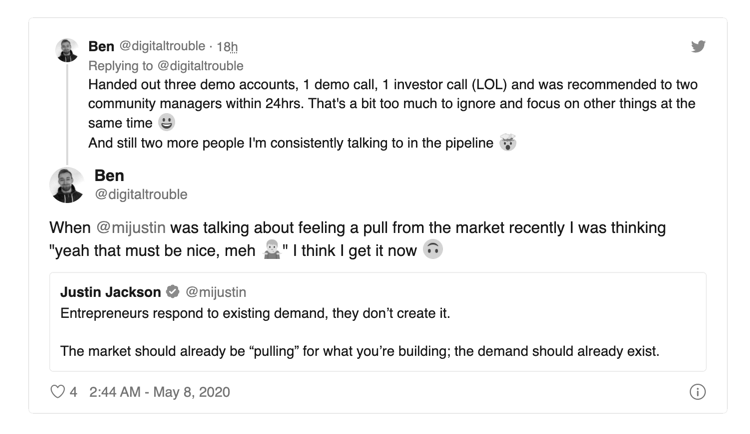

Cultivate good ideas. But don't be in a rush to execute on all of them; let the bad ideas fall away. Wait until you feel the strong pull of the market; then start executing.

This recently happened to my friend Ben:

Ben had been exploring numerous ideas, including a social link-sharing platform, and a Slack competitor. But now, after listening to folks who manage online communities, he's observed a need. And now he's going to take that hunch and focus on playgroup.community.

Ideas aren't easy. Ideas aren't cheap! Wait for a good one to come along before you start executing.

Cheers,

Justin Jackson

@mijustin