Should we always charge more?

These days, many people in the indie startup community will advise you to "charge more" for your product, but this isn't always the right advice.

Should you charge more?

For years, Rob Walling, Jason Cohen, and Patrick McKenzie have been advising startups to "charge more."

Early in bootstrapping's history, this was much-needed advice. It was something the community needed to hear. In 2006, Patrick McKenzie noticed that developers consistently "undervalued their software." In a 2012 newsletter, he sharpened this even more: "technical founders perceive code as being worth its cost and its cost to them is zero."

In talks and blog posts, bootstrappers challenged each other to test their pricing. It had a positive impact on many new entrepreneurs. Folks like Ruben Gamez increased their prices and saw good results.

But gradually, I feel like our community's discussion on pricing has devolved.

These days I hear only two words: "charge more."

I often hear this advice dispensed without context:

We've lost the nuance. We're treating "charge more" like a startup panacea.

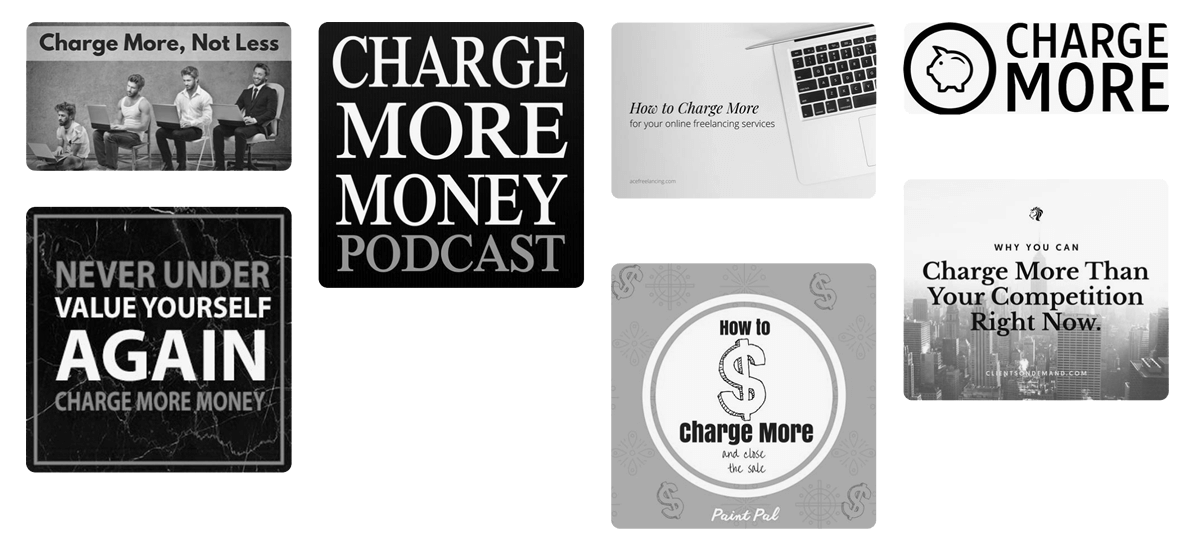

But pricing is complex. These six economics professors wrote a paper on it. Most of it looks like this:

Even bootstrappers used to write thousand-word blog posts to explore the topic.

But now it feels like we've replaced all that depth with a two-word meme.

It seems strange to me that folks give this advice without the relevant context. How are they so confident that "charge more" is right for this person's market and stage of business?

“The right advice at the wrong time is the wrong advice.” – Sean McCabe

My goal for this post is to have a balanced discussion about pricing software. Let's get into it.

The effect of competition on price

In SaaS, most niches have multiple competitors.

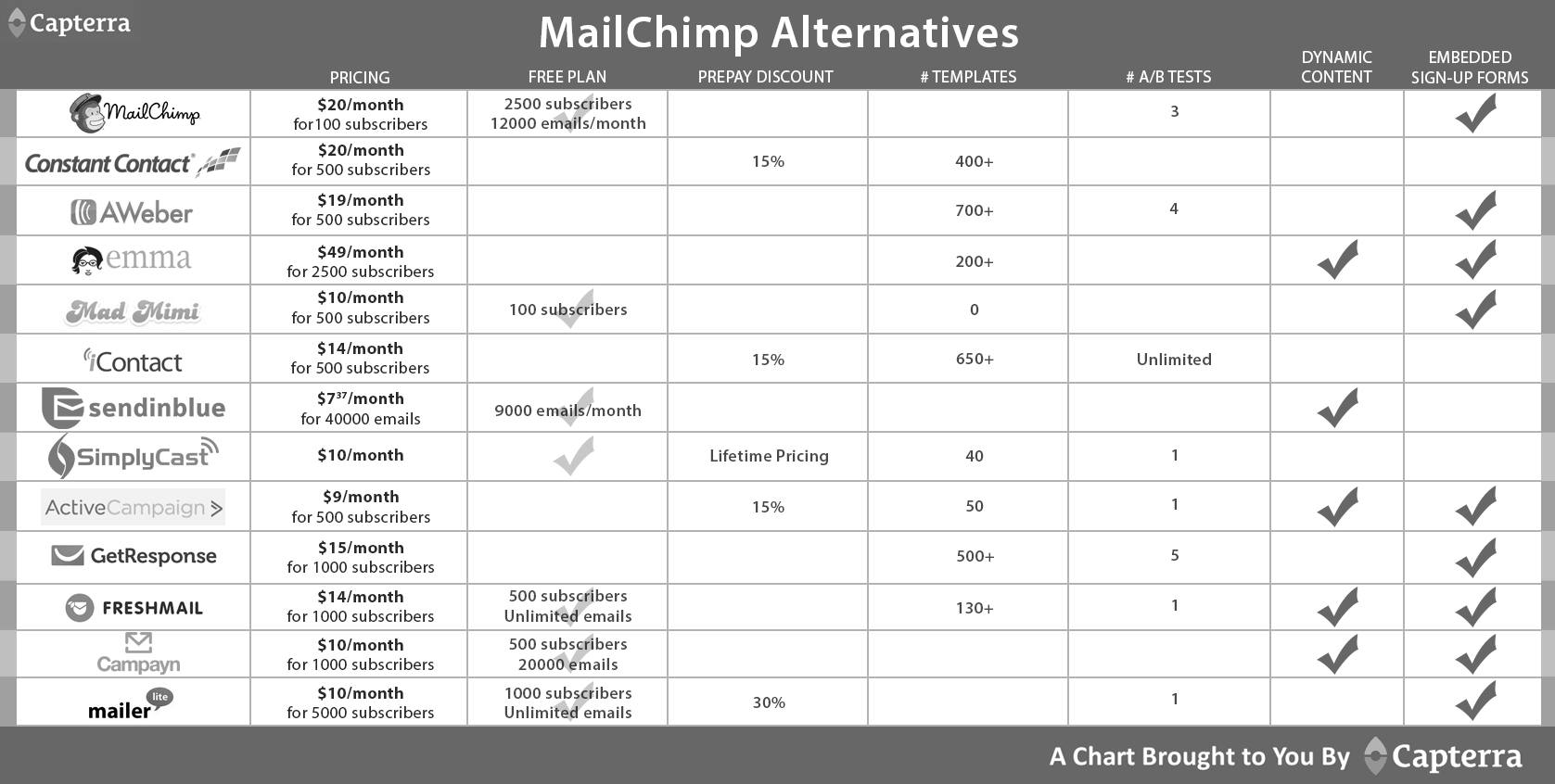

When MailChimp introduced its freemium plan in 2009, it rocked the ESP world. Suddenly, customers could have up to 500 subscribers for free. Campaign Monitor, who was charging $15/month for this, had to reduce its price to $9. Campayn decided to match MailChimp's offer (500 subscribers for free).

Some competitors, like ConvertKit, can charge marginally higher prices. But everyone's been anchored by Mailchimp's pricing. Unless they're going after a premium niche, no one is going to double their rate.

They won't double their price, because they know that customers do comparison shopping. If you have roughly the same features as MailChimp, but cost 2x as much, it's less likely that you'll get picked.

Pricing is hard at the beginning

Launching a new app in an existing market is difficult because your competitors are way ahead of you. They've built-up numerous advantages:

Brand-name recognition.

A marketing machine.

Tons of features.

SEO.

Building a new product is like running a marathon, but starting an hour after everyone else.

As a new product, you're asking customers to switch away from the incumbent. In their eyes, your app is untested, unproven, and has fewer features. Is now really the time to ask them to pay more?

Since launching our app (Transistor), we've learned that 38% of our customers switched to us from a competitor. They're mostly coming from Simplecast and Libsyn. At $19/month, our initial tier is already more expensive than theirs ($15 and $5, respectively). Would we have gotten as much traction if we'd started at $29, $39, $49? Judging from the conversations I've had with customers, the answer is "no."

In an episode of Startups for the Rest of Us, Rob Walling says:

The only time you can’t necessarily raise prices is if you have a bunch of competitors. If they’re implementing these features at a similar rate to what you are, you won't have enough differentiation. Customers will say, 'I can just switch over.'

Pricing depends on your startup's stage

The way you price your product depends a lot on your startup's stage:

The early days,

right before product-market fit,

after product-market fit,

and the growth stage.

Rob Walling comments:

In each of these stages, you have to approach things differently. In the very early days, I don’t know that you want to charge more. But you should charge something.

Currently, most of Transistor's revenue comes from our Starter plan:

This makes sense for our stage: we only launched eight months ago. We haven't yet built the features that will make our premium tiers more attractive.

We talked with Patrick Campbell (at Price Intelligently). He advised:

In your early stage, two things are essential: your customer focus and your value metric. If you can nail these two things (even if you get everything else wrong), you’re typically fine.

Right now, our focus at Transistor needs to be:

Understanding our customers,

and providing them with more value.

And we're still learning!

Initially, we thought our value metric for podcasts would be "monthly downloads." That is important to a lot of our users. But, there's a segment of our premium users who don't care about listener numbers. For them, value means something different.

We need time to understand our different customer segments, and what brings them value. After that, we can decide which segment(s) we want to pursue, and how to give them great results. And then, we can look at pricing.

Understanding value-based pricing

"Price based on value" is another misunderstood startup mantra.

Warren Buffet famously said:

"Price is what you pay, value is what you get."

He was talking about investing, but the line holds for pricing products too.

Lincoln Murphy describes it this way:

"Customers generally care only about their desired outcome. Value Pricing is knowing the value of your service as perceived by your target market."

For example, if you pay me $10,000, but I bring you $100,000 in new sales, that's a pretty good deal. You're getting 10x more value than what you paid.

But in practice, figuring out "value received" is more difficult.

Another example: imagine you're running a design agency and it's disorganized and chaotic. One day, you discover Basecamp. You try it out, and it magically everything gets better: you are calmer, your employees are more efficient, and your customers are happier.

How do you quantify the value you're getting from Basecamp? Is it worth $100 a month? $1,000? $10,000? The answer is subjective.

For many SaaS products, the value the customer receives is hard to quantify. You might say: "we save $x on salaries," or "this app saves us time," or "it helps us build our brand." But providing a direct correlation between "money paid" and "value received" isn't empirical.

"I paid $100 and got $1,000 back" has a clear cost/benefit outcome. But most of the time it looks more like this: "I paid $100 and now I feel like I'm making progress."

Value pricing is often based on a feeling. Does it feel like I'm getting a good deal as a customer?

Nathan Barry wrote this brilliant post where he highlights how it feels to get a good deal:

At ConvertKit we get so much value from Basecamp that if they doubled their price we wouldn’t blink. Really, they could 10x our price to $1,000 a month and they would still provide more value for us than we’d be paying.

Then he talks about a product on "the opposite end of the spectrum:"

Segment provides an incredible amount of value, but they charge a ton for it. The high value is equally matched by a high price, not leaving any surplus.

In this example, Segment is "charging more." Right now, Nathan is willing to pay their price, but he doesn't feel good about it. "We end up resenting a company that we’d normally love, " he says. It could be different, if they considered "leaving some value on the table."

Ryan Kulp wrote a blog post with a similar sentiment:

Last week I spent $10 at a national taco chain and I’m still shuddering at the expense. Economics tells us they're better because they maximized profitability. Problem is, I’ll never buy from them again.

Maybe you should charge less

We should pay attention to this idea of charging less for the value you provide. It's the flipside of "charge more," and it has its own advantages.

Tyler Tringas talked about some of the benefits here. I'll paraphrase for him:

By keeping prices low, you make renewing a no-brainer. You make switching 'not worth the effort.' You'll lower ARPU, but you'll get higher long-term retention.

In his blog post, Nathan Barry gave three possible benefits for lowering prices:

More referrals.

Faster organic growth.

Lower churn.

Ryan Kulp echoed these ideas too:

Let your customers think they got a great deal. They’ll tell friends about you, who then become new customers. And those customers will love you, because you’ll give them good deals too.

I'm not saying that "charge less" is right for you, any more than "charge more" is. But it's worth testing.

On Twitter, Aaron Chiandet told me about his company's price test results:

We put a large dent in churn by reducing the cost of our plans. We were able to retain AND acquire more users for a net gain. LTV shrunk a tad but CAC was still well below, so it was a no brainer for us.

Test pricing the right way

This brings us back to one of Patrick McKenzie's primary tenets:

Test your pricing!

If your business is at the right stage of its development, you should be testing your pricing.

But make sure you're testing the right things, over the right timeframe. Increasing your price might look good in the short term, but could be worse for revenue in the long-term.

Ruben Gamez brought this up on Twitter:

Over the years I've done a lot of price testing. Important: measuring impact through to churn (I've been surprised a couple of times). I've had pricing changes that seemed good at first (initial 60 days). But then churn increased on higher tiers or there were more downgrades to lower tiers. Also: pricing changes that seemed like a nice increase but overall have ended up with slightly lower LTV.

In his case, a price change resulted in him losing customers at a higher rate, and making less revenue. He wouldn't have noticed this trend if he hadn't tested the price over 60 days.

So, should I charge more, or charge less?

Generally, you want your price to reflect:

the value you give,

the market segment you're targeting,

the economy (weak/strong) you're in,

the stage of your startup.

"Charge more" can be good advice. But, depending on the context, so can "charge less."

The only way to know for sure? Seek to understand your customers better, give them as much value as you can, and then, test your pricing.

I hope this starts a broader discussion! Tell me what you think.

Cheers,

Justin Jackson

@mijustin